What we can learn from bats by Winona LaDuke

There are many old stories in Ojibwe culture. Those stories often tell of lessons brought to us by animals. There’s an old story about how the bat helped us win a lacrosse game and now that’s why the birds migrate. This time might be known as the time that the bat, or the bapakwaanaajiinh, taught us a lesson.

There are many old stories in Ojibwe culture. Those stories often tell of lessons brought to us by animals. There’s an old story about how the bat helped us win a lacrosse game and now that’s why the birds migrate. This time might be known as the time that the bat, or the bapakwaanaajiinh, taught us a lesson.

Written By: Winona LaDuke | Mar 16th 2020

It’s said that the coronavirus (COVID-19) originates from bats in China. Researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology found the genome in the virus found in patients was 96% identical to that of an existing bat coronavirus, according to a study published in the journal Nature. It’s not clear the intermediaries between bats and humans, but what is known is that the virus has traveled, and it's not done yet.

What does the bat teach us?

Well, first of all, it might teach us to slow down. That’s OK. Google and Amazon sent home their people. God only knows that their teams must have enough technology that they can work at home. And, what if that works out well, because people don’t have to commute, and can be happier and around their families.

Maybe there’s a lesson in this for some industries.

We learn about global trade. It turns out that we make a lot of stuff in China. We‘ve globalized our markets in such a way that if China closes down, a lot of stuff spins. Take the example of shrimp. Most restaurant shrimp are today farm raised in Scotland, shipped to China to be deveined and processed, then shipped to the U.S. to be served at the salad buffet. That seems like a lot of travel for a shrimp, if you ask me.

We learned that money is also fragile. There’s rich people crying over their investments. Investors continued to blame the spread and economic impact of the coronavirus for steep losses. They might want to invest in local, not global, economies.

Italian Premier Giuseppe Conte announced that all the country’s stores except pharmacies and groceries will be closed in a move deemed both necessary to safeguard human health and a threat to the country’s output.

RELATED

LaDuke: I retain my faith in beauty and in love

LaDuke: I'm a patriot to this land

Wall Street worries that such measures could tip the global economy into recession, especially if Washington decides the disease is rampant enough in the U.S. to warrant similar measures. The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. We learned that it might be good to have local food security, and make sure there’s toilet paper, because everyone is stocking up, and there might be a crisis.

We learned that we are not prepared for outbreaks of viruses of this scale. When the first coronavirus case showed up in Seattle, Dr. Helen Chu, an infectious disease expert, needed some questions answered. According to a New York Times story, she asked for help from state and federal officials and was denied. She tried for a month to get approvals, then pushed ahead, finding that the virus had already established itself. The lack of coordination by federal officials, gutted research programs and what I refer to as “white tape” slowed our response. While South Korea can test l0,000 people a day for the virus, the U.S. did not have that capacity. We are still scrambling, and time matters.

Here’s another challenge: we don’t have a national health plan, so 44 million people don’t have health insurance and are probably not going to go in and get checked.

We learned that we don’t need as much oil as we thought. According to Bloomberg News, China is turning back oil from Saudi Arabia. “Chinese refiners have reduced the amount of crude they’re turning into fuels by about 15%, and may deepen those cuts in coming weeks. State-owned and private processors have pared back refining by at least 2 million barrels a day…” The price of oil has plummeted, and the largest tar sands mining project in the world was cancelled. We just don’t need it; we never did. We learned that we are not in control of everything we think we are.

For me? I’m going to head to the sugarbush and slow down. That’s the place in the north country where sugar comes from a tree, with the medicines of spring. Getting outside, getting fresh air, smelling sap as it boils is pretty healthy.

Then there’s the pleasure of continuing a tradition from time immemorial. The Ojibwe maple sugar bush doesn’t need anything from China or from the rest of the world. That seems like a good idea to me.

I’m going to take lessons from the bats and do my best to be healthy.

I come from people who have survived small pox glaucoma, tuberculosis and gas chambers.

I’ll try and survive this.

A single bat can eat up to 1,200 mosquitoes in an hour and pollinate all sorts of life.

In Minnesota we have a bat called the Long Eared Bat, it’s special to the Northwoods.

I am going to be grateful for that bat, and the lessons I’ve learned.

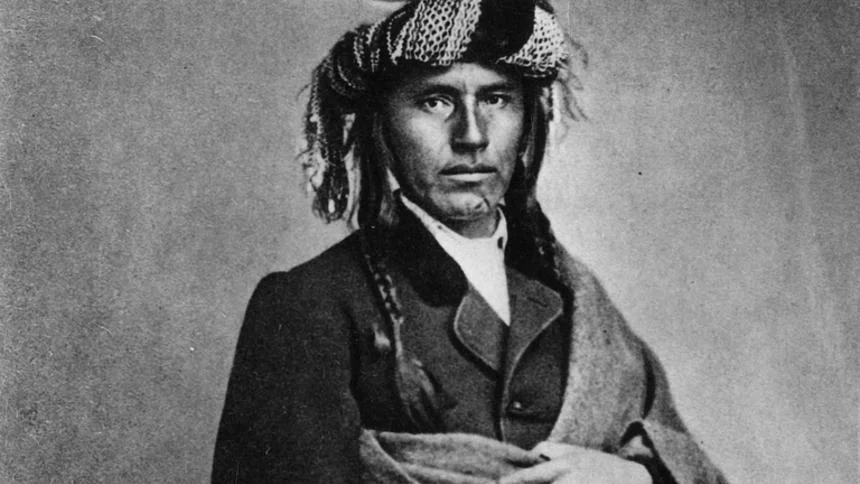

Hole in the Day, or Bug o ne giizhig Famed Ojibwe chief leaves checkered legacy 150 years after assassination

Famed Ojibwe chief leaves checkered legacy 150 years after assassination

Hole in the Day was one of the negotiators of the l867 treaty which created the White Earth Reservation, and most of his descendants came to live on this reservation. He was never allowed to live out his life in peace on White Earth, but was assassinated on the Gull River, near Crow Wing, in l868.

Famed Ojibwe chief leaves checkered legacy 150 years after assassination

By Gabriel Lagarde on Jun 27, 2018

"They said Hole-in-the-Day was like a big log in the road, too high to get over, too big to go around."

Or so the Dispatch reported Tuesday, Aug. 11, 1912, from the testimony of Kah-ke-gay-aush, 73, of Big Bend. At the time, Kah-ke-gay-aush was recounting the assassination of Chief Hole-in-the-Day the Younger—one of the most prominent and recognizable faces of the Ojibwe people in Minnesota, gunned down and executed by a band of assassins in the road on June 27, 1868, near the current site of the Fisherman's Bridge off Gull Lake. Each of his killers were reportedly rewarded a crisp $1,000 and a new house for the deed.

Wednesday, June 27, marks the 150th anniversary of the famed and controversial Ojibwe chief's death.

It was a moment in time that characterized the age—the relinquishing of the land from Native Americans to white settlers, a murky era when the Brainerd lakes area was part of a brand-new state barely a decade old, more of a wild frontier with conflicting authorities. There wasn't a city of Brainerd yet to call it the Brainerd lakes area in the first place.

Now, a century and a half later, a "big log on the road" may remain an apt description for the man—because, when one looks back at the history of the area, Chief Hole-in-the-Day remains something of an inescapable presence. His life and his death fundamentally shaped much of what the Brainerd lakes area is today, Brainerd historian Jeremy Jackson told the Dispatch during a phone interview, Tuesday, June 26—to say little of the ramifications for the Ojibwe people of Minnesota all the way to the present.

However, at the surface level, most people only come across him through his namesakes, he said.

"There's two lakes in the Brainerd lakes area named for him, there's Hole-in-the-Day Bay (on Gull Lake), there's a Hole-in-the-Day Drive up by Nisswa," Jackson said. "It's sometimes interesting to find out who's the person behind these names."

Who was Hole-in-the-Day the Younger? He was a chief who held sway and largely represented the interests of the Ojibwe in Minnesota—though, his local and strongest ties remained with the bands in what is now the Brainerd lakes area, said Anton Treuer, a professor of Ojibwe language at Bemidji State University who has written extensively on the subject.

"It was an impossible time for native people across the country. Some people, like the Cherokee, tried to accommodate, never fought and they still got marched off on the Trail of Tears. Some fought very famously, like the Apache or the Lakota, and they died and got pushed onto reservations and suffered horribly for that," Treuer said. "Hole-in-the-Day, in this difficult time, picked a different strategy. He did not simply accommodate and he did not simply fight—he was a tough diplomat in difficult circumstances."

At a time when Native American leaders were rapidly losing ground and bargaining power with the United States government, Treuer said, Hole-in-the-Day's firm and savvy brand of negotiating enabled him to protect his people's interests long after many other native communities were diminished and stripped of much of their sovereignty.

Jackson said Hole-in-the-Day frequently traveled to the White House and met with presidents face to face—often, he noted, in the role of a representative of all Minnesota Ojibwe.

"He was very well versed, I would say, in diplomacy and if he had to be the opposite of that, he could be a real strong warrior to represent the Indian people," said Ray Nelson, president of the Friends of Old Crow Wing.

As such, Hole-in-the-Day had a mixed reputation among the whites of his day, Nelson said—whether it was as a refined, welcoming figure who frequently entertained guests that traveled out to central Minnesota to meet him, or as a formidable and terrifying opponent, as evidenced by his role in the Dakota War of 1862.

His reputation among Native Americans and his own people, the Ojibwe, was polarizing as well.

"He had a two-story house while the rest of his people were descending into abject poverty. There was a feeling he was taking too much fat along with his deals," Treuer said. "He's not a good guy, he's not a bad guy, he's a good guy and a bad guy who's highly effective."

While he retained a powerful position in the area until his death—not only among the Ojibwe, but also the white traders, Indian agents and "mixed-blood" settlers in the settlement of Crow Wing—Hole-in-the-Day largely did this through engaging in blatant corruption that typified the area for decades. He invested into and benefited from questionable partnerships with local authorities, Treuer said, while he lined his own pockets.

At the same time, he could be recklessly ambitious and overstep the limits of his authority, Treuer added—Hole-in-the-Day's insistence he was the chief of all the Minnesota Ojibwe created rivals of his contemporaries, and there were cases, such as his misstep as posing as the unauthorized representative of the Mille Lacs Band during the treaty talks of 1867, that further strained his relationship with his fellow Ojibwe.

"When I was researching his assassination, the question wasn't, 'Who actually had motive,' it was, 'Who didn't have motive,'" said Treuer. He noted the famed Ojibwe chief contended with white and biracial settlers, Catholic missionaries, the United States government, the Sioux, historical figures like Clement Beaulieu and Charles Ruffee, as well as many of his fellow Ojibwe at different points in his life.

In 1912, the Dispatch reported it was generally accepted Hole-in-the-Day died because of his opposition to allowing "mixed-bloods," or biracial people, into the newly formed White Earth Reservation. At the time of his death, he was starting another journey eastward to meet in Washington, D.C., to renegotiate the terms of his people's agreements in that regard.

Documents at the time point to figures like Ruffee and Beaulieu, as well as a number of other prominent Crow Wing village families, as the instigators of the murder.

Treuer said he sees Hole-in-the-Day's death as a coup d'etat by the biracial settlers and white Indian agents the chief dealt with for years—men like Beaulieu and Ruffee, who enjoyed a fruitful partnership with Hole-in-the-Day when he controlled vast swaths of land during the fur trade; who now, as a result of these treaties, had little land left to offer and not much else to barter with when timber, mining and agriculture were coming to the forefront.

With his death, Treuer said, the White Earth Reservation didn't see Native American leadership until the native tribes were consolidated under their own authority in the 1930s.

With much of the area's wealth, timber and land under his control, Beaulieu and his cohorts would go on to found Crow Wing County—named like the village he founded, which collapsed, ironically, Treuer said, when Beaulieu overestimated his own bargaining power and pushed the railway and timber tycoons to form a new trade hub in the area.

Hole in the Day was one of the negotiators of the l867 treaty which created the White Earth Reservation, and most of his descendants came to live on this reservation. He was never allowed to live out his life in peace on White Earth, but was assassinated on the Gull River, near Crow Wing, in l868.