Amid Blackout, a California Tribal Village Kept Lights On With Solar Energy by Winona LaDuke

Energy leadership is coming from Native people. A Deal With Future Generations

Building renewable energy projects is about more than just post-fossil fuel economics. It’s about the future of electrification in this country. Think of it this way: This past month, Pacific Gas and Electric, northern California’s largest northern utility, blacked out 500,000 homes because of forest fires; last year’s Paradise Fire was actually caused by PG&E Lines. As fires raged, fanned by climate change and poor infrastructure, there were still lights on at the Blue Lake Rancheria, a Wiyot, Yurok and Hupa village near Eureka, California – with a megawatt of solar and a battery backup system.

PUBLISHED November 16, 2019

October’s 383,000-gallon spill of the Keystone Pipeline in Edinburgh, North Dakota reveals the pipeline for what it is: a deal with the devil. For those of us who live in the land of lakes, just imagine what 383,000 gallons of oil will do to the Hay Creek, Fishhook Lake watershed, and what “clean up” will look like. There’s no way to clean up or protect that aquatic ecosystem. There are no fish, wild rice or life after an oil spill.

That’s what a deal with the devil looks like. While Enbridge talks about the need for a new safe pipeline, the fact is that the Keystone pipeline is not even 10 years old. It is a new pipeline, and it still leaked. In fact, the October catastrophe was its second major leak; the 2017 pipeline rupture sent 407,000 gallons spewing into South Dakota groundwater.

North Dakota has sold its water and soul to the oil companies. Three years ago, a study by Duke University found:

Accidental wastewater spills from unconventional oil production in North Dakota … caused widespread water and soil contamination…. Researchers found high levels of contaminants and salt in surface waters polluted by the brine-laden wastewater, which primarily comes from fracked wells. Soil at spill sites was contaminated with radium. At one site, high levels of contaminants were detected in residual waters four years after the spill occurred.

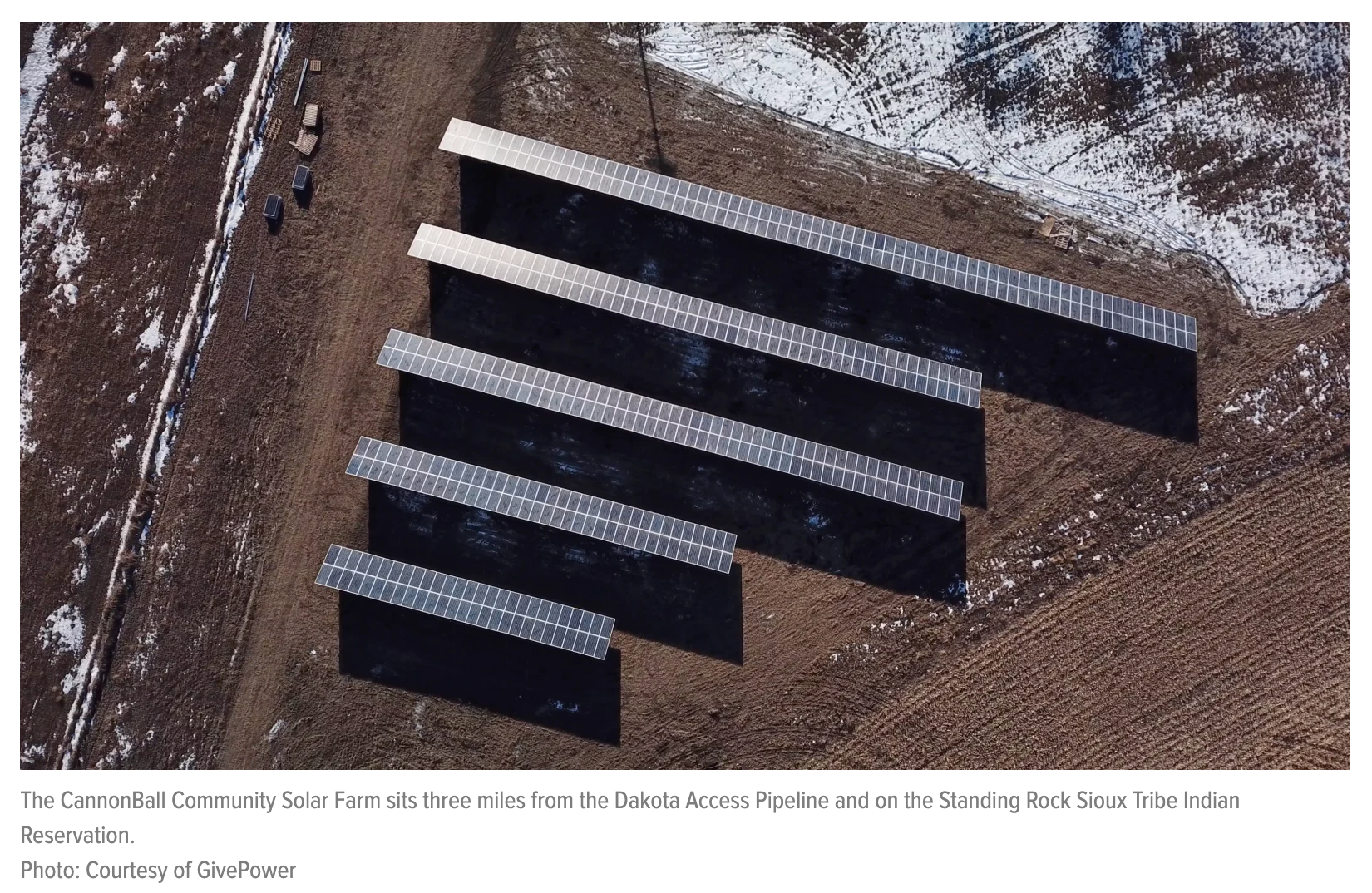

In the meantime, the Lakota are making deals with the Creator for a better future. The first solar farm in North Dakota went up this year — the Cannon Ball Community Solar Farm on the Standing Rock Reservation. Born from the ashes of the Standing Rock battle over the Dakota Access Pipeline, the Cannon Ball solar project shows us all what the future looks like.

This past summer, many veterans of the siege at Standing Rock returned, this time to celebrate a victory: the establishment of the solar farm. Movie stars Mark Ruffalo (The Avengers) and Shailene Woodley (Big Little Lies) and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-Hawaii) all came to Standing Rock. The Cannon Ball Community Solar Farm provides the Standing Rock Reservation with 300 kilowatts and will save the community an estimated $7,000 to $10,000 annually in energy costs.

The solar farm is just the beginning of energy sovereignty at Standing Rock. Cody Two Bears, executive director of Indigenized Energy and former Standing Rock tribal council member, says more projects are on their way. In the midst of Standing Rock’s battle with the Dakota Access Pipeline, the seeds of solar were planted.

“It’s one thing to protest about it, to talk about it, but now we got to be about it,” Two Bears said in an interview with Truthout. The solar farm was connected to the grid in February, and went live in August, powering the Cannon Ball Youth Center and the Veterans Memorial Building, where thousands of veterans who came out to support the pipeline opponents stayed in 2016.

In comparison, the state of North Dakota as a whole lags behind, with no utility scale solar, and with immense, unrealized wind potential.

Energy leadership is coming from Native people.

A Deal With Future Generations

Building renewable energy projects is about more than just post-fossil fuel economics. It’s about the future of electrification in this country. Think of it this way: This past month, Pacific Gas and Electric, northern California’s largest northern utility, blacked out 500,000 homes because of forest fires; last year’s Paradise Fire was actually caused by PG&E Lines. As fires raged, fanned by climate change and poor infrastructure, there were still lights on at the Blue Lake Rancheria, a Wiyot, Yurok and Hupa village near Eureka, California – with a megawatt of solar and a battery backup system.

Adopting a climate action plan in 2008, the tribe mobilized every resource at its disposal to advance a leading-edge strategy for eliminating its carbon footprint while bolstering climate resiliency. To date, the Tribe has reduced energy consumption by 35%and reduced greenhouse gas emissions 40%, utilizing biodiesel to power public buses and aggressive energy efficiency measures. Back in the Obama administration, Blue Lake was recognized as one of 16 communities designated as White House Climate Action Champions.

The grid went down, and the tribe still had solar. That’s a covenant, a deal with future generations. Change comes, it’s a question of who controls the change.

Looking down the barrel of a bad pipeline, I know that we don’t need to make a deal with the devil. North Dakota and Enbridge: Go grow your food with oil — I’m going to grow my gardens with water; I’m going to commit to solar and renewables. Let’s see who will eat.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission

The last tar sands pipeline by Winona LaDuke

In early June, I traveled to Enbridge’s Shareholder meeting in Calgary, in Alberta Canada. Outside, laid off oil workers screamed, “Build that Pipe” over a bullhorn, and asked people to honk if they supported Canadian oil. Those tar sands workers will likely never have jobs in the industry again – economists, and even the oil fairy government of Alberta, are sobering up to the Boom Bust economy of energy projects. It’s the bust and there is no boom in sight. That’s the problem. It’s really a race to the bottom and to the end – that is to be the last tar sands pipeline. For the past four years Canada has been trying to run tar sands pipelines through the US, to the Coast, to anywhere, and it has not gone well. And it’s not going to, and here are the reasons why ...

The Circle News: The last tar sands pipeline

by Winona LaDuke

In early June, I traveled to Enbridge’s Shareholder meeting in Calgary, in Alberta Canada. Outside, laid off oil workers screamed, “Build that Pipe” over a bullhorn, and asked people to honk if they supported Canadian oil. Those tar sands workers will likely never have jobs in the industry again – economists, and even the oil fairy government of Alberta, are sobering up to the Boom Bust economy of energy projects. It’s the bust and there is no boom in sight. That’s the problem. It’s really a race to the bottom and to the end – that is to be the last tar sands pipeline. For the past four years Canada has been trying to run tar sands pipelines through the US, to the Coast, to anywhere, and it has not gone well. And it’s not going to, and here are the reasons why:

Tar sands oil is too expensive. Say you had the most expensive oil in the world and it was landlocked in northern Alberta. Put it this way, Middle eastern conventional oil comes in at $26 a barrel, and there’s about 800 billion barrels out there, that’s according to Rystad Energy, international oil analysts. Tar sands oil comes in at about $83 a barrel, and there’s not much of it. That’s the reality.

Big oil doesn’t really care about Alberta’s financial problems. “Alberta governments have suffered from a type of budgetary delusion over the past decade, a phenomenon that drives up spending and sent debt levels soaring,” Newly elected Alberta Premier Jason Kenney wrote in the Calgary Herald. “For decades the choice for Alberta governments seemed simple: the province overspent budgets and trusted that energy revenues would fill the gap.”

“Alberta is in a very deep fiscal hole.” Kenney continued, “this… cannot continue. My belief is that we won’t see another boom .This is it, this is the new reality.”

Tar sands oil is the dirtiest oil in the world. This stuff is basically asphalt, mixed with a bunch of toxic stuff. The oil needs lots of water and chemicals to bring it out. Nasty stuff really. That reality is leading to divestment – fossil fuels divestment is now at $7 trillion. In the time of climate crisis, even the big insurers are ready to move on.

No one wants a tar sands pipeline. Two years ago there were five tar sands pipeline projects proposed – Enbridge had two, Trans Canada had two and Kinder Morgan had one. TransCanada’s failed Energy East Pipeline – the longest proposed pipeline from Alberta to New Brunswick was not approved by Canada’s National Energy Board. Neither was Enbridge’s Northern Gateway, which they planned to run through pristine watersheds into a set of fjords in northern British Columbia. Both those projects failed in 2017. None of the remaining pipeline projects are doing well. Ill fated Kinder Morgan pipeline – Trans Mountain, is enmeshed in litigation, despite it’s being nationalized by the Trudeau Administration in August, 2018. That was just the day before the Canadian Federal Appeals Court declared all permits null and void.

That leaves two pipelines fighting to be the last tar sands pipeline: Line 3 and Keystone XL (or KXL Pipeline) which is buried in legal challenges. Keystone faces the federal courts in Montana, and Line 3 faces the courts in Minnesota, as well as a delay. Costly stuff. With the new cost overruns announced by Enbridge, analysts believe it will be the most expensive pipeline never built. The last tar sands pipeline was built already. That’s the skinny – it was called the Alberta Clipper.

Enbridge Line3 Tar Sands Pipeline Storage Yard in Red Lake Nation Territory - Plummer, MN

Canada now has more people employed in renewables than in all fossil fuels. The math does not add up for the tar sands. How broke do we want to be? And, how many people do we want to arrest and injure in Minnesota to address Canada’s lack of a diversified economic plan?

The stars, G5 cell towers, and electromagnetic radiation exposure by Winona LaDuke

We need to rethink just blindly adopting technology for convenience. If we want this new faster connection, what we may want is more expensive but less damaging: a fiber optic system to wires (even faster), not waves going through living bodies. It’s ok for machines but not biology.

“In 2012, the General Accountability Office found that the existing standards may not reflect current knowledge and recommended that the FCC formally reassess its standards. The FCC’s standards address only one aspect of potential harm from electromagnetic radiation – heat. The current standards do not address other ways in which exposure to increasing electromagnetic radiation from wireless communications can harm human health, as well as the natural systems around us on which all life depends.” (5G and the FCC: 10 Reasons Why You Should Care by Sharon Buccino. 2019)

The concern is a risk of cancer, particularly in heart and brain cells, according to the National Toxicology Program in a 2018 study. I think that most of us know that intuitively you cannot get zapped continuously without consequence. I think that Genie should stay in the bottle for a few years. While you can no longer see the stars in many places, where I live they are clearly in sight. They remind me of my ancestors, the air, and the navigation tools needed for the time ahead.

The Circle News: The stars, G5 cell towers, and electromagnetic radiation exposure by Winona LaDuke

Our ancestors navigated by the stars. Today most of us need a cell phone to know where we are going. That’s sobering. We are out of touch. That’s not to say I am going to be able to navigate by stars anytime soon, but I still like the directions of “turn at this barn”, or “the lake on the left”. And I like maps. They tell a story and give me a visual which does not change.

What I like may be changed forever by new technology. G5 cell service – promised by Verizon, ATT, TMobile and Virgin – speeds up the world and adds a lot of towers, up to 800,000 new towers. That’s a lot of cell coverage. The big companies, Verizon and ATT, already offer G5 service in some urban areas and the companies are promising to bring it to the rural north. My son will be able to stream games, movies, and all more quickly while sitting on the couch. How fabulous is that?

Well, I think it’s a bad idea. G5 adds to our world another level, a higher level of electromagnetic radiation exposure, which is damaging not only to our health but to the world we live in. This service requires lots of new towers, closer together – in some places, once every l2 houses. In short, lots of money for the companies and possibly lots of risk. Add to that the speed in which this is to be deployed, without much of a look at the environmental and cultural impacts, and the problems compound.

Take the birds for example. There used to be millions of them. Fields full of geese, ducks, migratory birds, lakes echoing the sounds of these relatives. Take a good look. They are no more. Bird populations are plummeting quickly in North America – a 40% decline. In May, I traveled to New York City. Once the pigeons would make you crazy. Today there are none. Really, there are no birds. Maybe that’s a result of the insect Armageddon, since we have 50% or more loss in bugs. And birds eat bugs. Maybe it’s because young people do not care for pigeons like their elders who fed them. Maybe it’s because they commit mass suicide, or die offs. Or maybe it’s the 5G which now serves Manhattan.

It’s probably a combination of all. But what if we could roll back one of those, or maybe just have 5G Free Zones, like a few places where instant messaging and streaming doesn’t work. It turns out a number of cities – from Geneva Switzerland (the Swiss are definitely some technology people) to Petaluma, California – are opposing or stopping 5G installations. A federal lawsuit filed by 19 Native nations and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) asks for the same questions. Tribes, including the Seminole, Blackfeet, Rosebud Lakota, Crow Creek Dakota and others are concerned about the number of cell towers required for 5G and their impact on sacred sites, and traditional territories, while others are concerned about the health impact.

To be more specific, according to the legal case filed by the tribal governments and the NRDC (Case No. 18-1129, United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit), “Infrastructure supporting over 400,000,000 cellular telephones is perhaps the United States’ largest interconnected engineering structure. Existing technology uses large, widely-spaced towers. Carriers envision new networks with smaller towers, perhaps fifty feet tall, placed much closer together, creating smaller area coverage for each cell than existing technology. The FCC [Federal Communications Commission] expects mobile operators to build 55,000 new cell sites in the near term.”

That’s a lot of cell towers. We will be paying for those for sure. Maybe we need to look at where those would go. It turns out this will impact many Indigenous peoples. Native nations have tribal lands, sacred sites and cultural areas outside of present reservation boundaries. That’s, in part, why there is a formal consultation process. It also has to do with legal trust responsibility. The FCC, in fast tracking approval for the 5G network infrastructure, has determined that complying with federal regulations like the National Historic Preservation Act isn’t necessary. As the complaint notes, “The FCC’s concludes that Section 106 consultation is without serious value.” That is a pretty large problem for Native people.

Other groups, particularly environmental groups, are concerned about the health impacts of the 5G network on the natural world. Studies looking at the impact of electromagnetic pollution on wildlife have raised concern. One scientific review notes, “Phone masts located in their living areas are irradiating continuously some species that could suffer long-term effects, like reduction of their natural defenses, deterioration of their health, problems in reproduction and reduction of their useful territory through habitat deterioration.” (Electromagnetic pollution from phone masts. Effects on wildlife, by Alfonso Balmori. 2009)

The research has been underway for awhile, but I was too busy streaming my Netflix to read much. In September of 2017, more than 180 scientists and doctors from 35 countries, recommended a moratorium on the roll-out of the fifth generation, 5G, for telecommunication until potential hazards for human health and the environment are fully investigated by scientists. The scientists want to make sure that the research is conducted independent from industry or corporate influence.

This is the skinny: 5G means a lot more cell towers, on top of the 2G, 3G, 4G, Wi-Fi, etc. for telecommunications already in place. While Verizon continues to eat up more of my budget, part of it is that 5G will require many more antennas, with a full-scale implementation resulting in antennas every 10 to 12 houses in urban areas. It means we all get zapped, you will not be able to avoid exposure. The studies show that there are increased cancer risks, cellular risk, genetic damages and a bunch of other lousy stuff.

Add to that “10 to 20 billion connections” (to refrigerators, washing machines, surveillance cameras, self-driving cars and buses, etc.) all parts of the “Internet of Things.” That’s the same internet that I love so dearly, from smart phones to smart grid. So, what am I thinking? Take your eyes off that cell phone, or maybe it’s your IPAD, and just take a look around and breathe.

We need to rethink just blindly adopting technology for convenience. If we want this new faster connection, what we may want is more expensive but less damaging: a fiber optic system to wires (even faster), not waves going through living bodies. It’s ok for machines but not biology.

“In 2012, the General Accountability Office found that the existing standards may not reflect current knowledge and recommended that the FCC formally reassess its standards. The FCC’s standards address only one aspect of potential harm from electromagnetic radiation – heat. The current standards do not address other ways in which exposure to increasing electromagnetic radiation from wireless communications can harm human health, as well as the natural systems around us on which all life depends.” (5G and the FCC: 10 Reasons Why You Should Care by Sharon Buccino. 2019)

The concern is a risk of cancer, particularly in heart and brain cells, according to the National Toxicology Program in a 2018 study. I think that most of us know that intuitively you cannot get zapped continuously without consequence. I think that Genie should stay in the bottle for a few years. While you can no longer see the stars in many places, where I live they are clearly in sight. They remind me of my ancestors, the air, and the navigation tools needed for the time ahead.

Navajo Technical University confers first honorary doctoral degree to John Pinto

Navajo Technical University confers first honorary doctoral degree to John Pinto

CROWNPOINT — When recapping his six year journey to earn a bachelor's degree at Navajo Technical University, Darrick Lee called the experience a "privilege."

Graduates heard an inspiring speech by Winona LaDuke, an internationally renowned activist for the environment and for social justice.

LaDuke is Anishinaabe and executive director of Honor the Earth, an organization she co-founded with Amy Ray and Emily Salier of the music group, Indigo Girls.

In her remarks, she reflected on the energy transition the Navajo Nation faces and how the graduates will take the lead in developing that change, including investment in solar and wind projects.

"No time like the present to rebuild your energy economy," she said.

She said now is the time to end the injustice done by energy developers to Native peoples, including using the land to produce energy for urban populations while nearby households remain without electricity.

"Your nation will be a leader in this. I see this and know this. We are all counting on you to do the right thing," LaDuke said.

Noel Lyn Smith covers the Navajo Nation for The Daily Times. She can be reached at 505-564-4636 or by email at nsmith@daily-times.com.

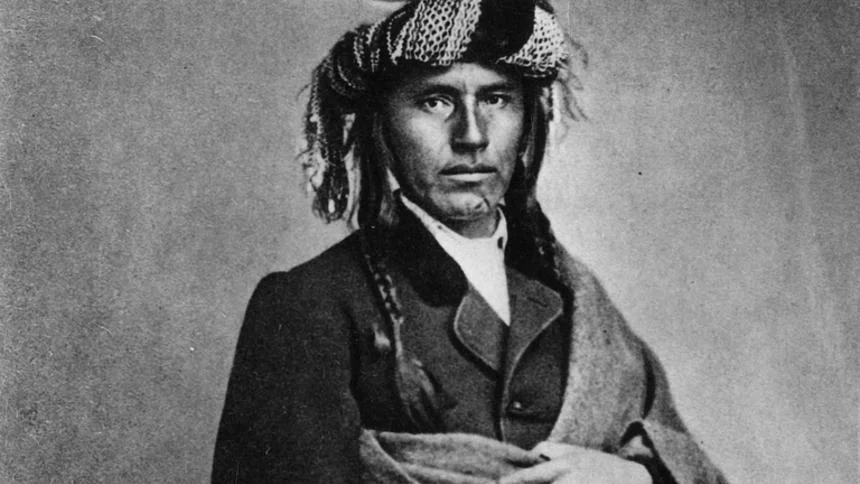

Hole in the Day, or Bug o ne giizhig Famed Ojibwe chief leaves checkered legacy 150 years after assassination

Famed Ojibwe chief leaves checkered legacy 150 years after assassination

Hole in the Day was one of the negotiators of the l867 treaty which created the White Earth Reservation, and most of his descendants came to live on this reservation. He was never allowed to live out his life in peace on White Earth, but was assassinated on the Gull River, near Crow Wing, in l868.

Famed Ojibwe chief leaves checkered legacy 150 years after assassination

By Gabriel Lagarde on Jun 27, 2018

"They said Hole-in-the-Day was like a big log in the road, too high to get over, too big to go around."

Or so the Dispatch reported Tuesday, Aug. 11, 1912, from the testimony of Kah-ke-gay-aush, 73, of Big Bend. At the time, Kah-ke-gay-aush was recounting the assassination of Chief Hole-in-the-Day the Younger—one of the most prominent and recognizable faces of the Ojibwe people in Minnesota, gunned down and executed by a band of assassins in the road on June 27, 1868, near the current site of the Fisherman's Bridge off Gull Lake. Each of his killers were reportedly rewarded a crisp $1,000 and a new house for the deed.

Wednesday, June 27, marks the 150th anniversary of the famed and controversial Ojibwe chief's death.

It was a moment in time that characterized the age—the relinquishing of the land from Native Americans to white settlers, a murky era when the Brainerd lakes area was part of a brand-new state barely a decade old, more of a wild frontier with conflicting authorities. There wasn't a city of Brainerd yet to call it the Brainerd lakes area in the first place.

Now, a century and a half later, a "big log on the road" may remain an apt description for the man—because, when one looks back at the history of the area, Chief Hole-in-the-Day remains something of an inescapable presence. His life and his death fundamentally shaped much of what the Brainerd lakes area is today, Brainerd historian Jeremy Jackson told the Dispatch during a phone interview, Tuesday, June 26—to say little of the ramifications for the Ojibwe people of Minnesota all the way to the present.

However, at the surface level, most people only come across him through his namesakes, he said.

"There's two lakes in the Brainerd lakes area named for him, there's Hole-in-the-Day Bay (on Gull Lake), there's a Hole-in-the-Day Drive up by Nisswa," Jackson said. "It's sometimes interesting to find out who's the person behind these names."

Who was Hole-in-the-Day the Younger? He was a chief who held sway and largely represented the interests of the Ojibwe in Minnesota—though, his local and strongest ties remained with the bands in what is now the Brainerd lakes area, said Anton Treuer, a professor of Ojibwe language at Bemidji State University who has written extensively on the subject.

"It was an impossible time for native people across the country. Some people, like the Cherokee, tried to accommodate, never fought and they still got marched off on the Trail of Tears. Some fought very famously, like the Apache or the Lakota, and they died and got pushed onto reservations and suffered horribly for that," Treuer said. "Hole-in-the-Day, in this difficult time, picked a different strategy. He did not simply accommodate and he did not simply fight—he was a tough diplomat in difficult circumstances."

At a time when Native American leaders were rapidly losing ground and bargaining power with the United States government, Treuer said, Hole-in-the-Day's firm and savvy brand of negotiating enabled him to protect his people's interests long after many other native communities were diminished and stripped of much of their sovereignty.

Jackson said Hole-in-the-Day frequently traveled to the White House and met with presidents face to face—often, he noted, in the role of a representative of all Minnesota Ojibwe.

"He was very well versed, I would say, in diplomacy and if he had to be the opposite of that, he could be a real strong warrior to represent the Indian people," said Ray Nelson, president of the Friends of Old Crow Wing.

As such, Hole-in-the-Day had a mixed reputation among the whites of his day, Nelson said—whether it was as a refined, welcoming figure who frequently entertained guests that traveled out to central Minnesota to meet him, or as a formidable and terrifying opponent, as evidenced by his role in the Dakota War of 1862.

His reputation among Native Americans and his own people, the Ojibwe, was polarizing as well.

"He had a two-story house while the rest of his people were descending into abject poverty. There was a feeling he was taking too much fat along with his deals," Treuer said. "He's not a good guy, he's not a bad guy, he's a good guy and a bad guy who's highly effective."

While he retained a powerful position in the area until his death—not only among the Ojibwe, but also the white traders, Indian agents and "mixed-blood" settlers in the settlement of Crow Wing—Hole-in-the-Day largely did this through engaging in blatant corruption that typified the area for decades. He invested into and benefited from questionable partnerships with local authorities, Treuer said, while he lined his own pockets.

At the same time, he could be recklessly ambitious and overstep the limits of his authority, Treuer added—Hole-in-the-Day's insistence he was the chief of all the Minnesota Ojibwe created rivals of his contemporaries, and there were cases, such as his misstep as posing as the unauthorized representative of the Mille Lacs Band during the treaty talks of 1867, that further strained his relationship with his fellow Ojibwe.

"When I was researching his assassination, the question wasn't, 'Who actually had motive,' it was, 'Who didn't have motive,'" said Treuer. He noted the famed Ojibwe chief contended with white and biracial settlers, Catholic missionaries, the United States government, the Sioux, historical figures like Clement Beaulieu and Charles Ruffee, as well as many of his fellow Ojibwe at different points in his life.

In 1912, the Dispatch reported it was generally accepted Hole-in-the-Day died because of his opposition to allowing "mixed-bloods," or biracial people, into the newly formed White Earth Reservation. At the time of his death, he was starting another journey eastward to meet in Washington, D.C., to renegotiate the terms of his people's agreements in that regard.

Documents at the time point to figures like Ruffee and Beaulieu, as well as a number of other prominent Crow Wing village families, as the instigators of the murder.

Treuer said he sees Hole-in-the-Day's death as a coup d'etat by the biracial settlers and white Indian agents the chief dealt with for years—men like Beaulieu and Ruffee, who enjoyed a fruitful partnership with Hole-in-the-Day when he controlled vast swaths of land during the fur trade; who now, as a result of these treaties, had little land left to offer and not much else to barter with when timber, mining and agriculture were coming to the forefront.

With his death, Treuer said, the White Earth Reservation didn't see Native American leadership until the native tribes were consolidated under their own authority in the 1930s.

With much of the area's wealth, timber and land under his control, Beaulieu and his cohorts would go on to found Crow Wing County—named like the village he founded, which collapsed, ironically, Treuer said, when Beaulieu overestimated his own bargaining power and pushed the railway and timber tycoons to form a new trade hub in the area.

Hole in the Day was one of the negotiators of the l867 treaty which created the White Earth Reservation, and most of his descendants came to live on this reservation. He was never allowed to live out his life in peace on White Earth, but was assassinated on the Gull River, near Crow Wing, in l868.

What is it about that Lateral Oppression?

The challenges we face as Indigenous women in North America are related to the challenges faced by women elsewhere; and we need true allies.

On White Feminists

What is it about that Lateral Oppression? I want to speak out on some white feminists. While I fully understand the critique of the privileging of white feminists and their ability, historically, who feel that they can speak on our behalf: this is not always the case. I think that as Native women we need allies, and those allies are of all colors; and the question is the relationship. In this case, Eve Ensler of V Day is a good target- because of her international profile, however, my experience with Eve and V Day is positive, nurturing and continues. I have worked with her, traveled with her, and shared coffee and stories with her. At this point I am standing with her.

Let me back up. I am not going to credential myself as a Native feminist. I am going to say that I’ve spent my whole life working on the issues that impact our communities, and Native women. For two decades I was a board Co-chair of the Indigenous Women’s Network, and I advocate for the status protection and furtherance of Native women. I’ve faced down completely privileged white women, aggressive Black women, and faced my own community, if I disagree. What I want is a positive future - ji misawaabanaaming.

As a writer and journalist, I often share stories. Those stories are told to me, or I am asked to tell those stories. I don’t’ tell stories, unless someone wants me to share their story. That is the ethic. From experience in working with Eve Ensler, I know that she shares those ethics. She has come to events for us, to raise awareness on the link between the exploitation of the fossil fuels industry and sex trafficking - last year we did an amazing event on this, and she has supported our work at Honor the Earth in the arena of environmental justice and Native women. I don’t think that the Indian Country Today piece targeting Eve was fair; although the general critique is essential.

The challenges we face as Indigenous women in North America are related to the challenges faced by women elsewhere; and we need true allies.

Winona LaDuke, Anishinaabe, is an American Indian activist, environmentalist, economist and writer.

By: Winona LaDuke

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2016/08/10/white-feminists

The Last Minnesota Indian Conflict - Interesting history connected to Round Lake

The Last Minnesota Indian Conflict: Through the hard work of Skip-in-the-Day and other Ojibwe Leaders and warriors, a Pine Point merchant, and other honest people this fraud was revealed. The Band received the correct payment and corrections in the dead and down pine policy were made. This ended the conflict at Round Lake, but not the conflicts coming at the White Earth Band of Ojibwe. For the next big manipulation came with trying to “Open up the Reservation.”

Within the history of Minnesota there are a series of tribal conflicts identified as “Uprising”, “Wars”, “Conflicts”, “Trouble”, and “Outbreaks.” The ability of tribal governments to deal with problems and resolve issues so that they can protect their members is a very complex.

The United States system of dealing with tribal government’s problems has many ways to be manipulated. This manipulation of the United States system that protects tribal people has happen many times. When the protection system failed and tribal people were being hurt there had to be a recourse.

At different points the only resolution was armed conflict.

In Minnesota this last armed Band conflict occurred in 1901 on the White Earth Reservation at a place called Round Lake. Round Lake today is known as East Round Lake. The Otter Tail River begins in Elbow Lake in Becker County which is just north of Round Lake, and suitable for driving pine logs. Over the winter of 1900-01 a series of logging company were authorized to cut pine on the White Earth Reservation in the area around Round Lake. The Bureau of Indian Affairs authorized the cutting of dead and down pine trees around Round Lake. The Band leader Skip-in-the-Day and other Indians at Round Lake reviewed the Bureau’s Superintendent Sullivan estimate of the pine cut and found that live trees had been cut and the estimates were in error. The Minneapolis Journal of May 11, 1901 printed the following.

“On May 6 Special Agent McComas promised them a re-scale and Joseph Farr, who rescaled the cut at other places, is now on his way to White Earth to check up Superintendent Sullivan's estimate. McComas' letter to the Indians is as follows: United States Indian Service, White Earth Indian Agency, Minnesota, May 6, 1901.— Skip-in-the-day and Other Indians —You are notified that I have this day listened to all that has been said by you In regard to the fact that you are not satisfied with the- scale of the logs that have been cut from your reservation this last season, and that I have this day sent to the honorable commissioner of Indian affairs in Washington a telegraphic message asking him to send here at once an expert government timber sealer to go over the entire ground of the logging camps with a man selected by you to determine whether or not they have been properly scaled and paid for. You will be notified when this man comes.” —Eugene McComas, Special Indian Agent.

The plot thickens as now a Special Indian Agent was investigating this matter. The logging camps wanted to get the pine they cut down the river and the spring was the best time to drive the logs. They were pressuring to move the logs.

“Park Rapids, Minn., May 11.—Traig, a merchant of Pine Point, on the White Earth Indian reservation, was here last night and confirmed the report that the Indians are congregating at Round lake, where millions of feet of logs have been banked. The Indians are excited, but no feeling is shown against resident whites, and the settlers are not likely to be troubled, whatever happens. Their quarrel is with the logging company and with the government which has permitted such extensive operations under the "dead and down" law. They feel they have been unjustly treated, and it is significant that public sentiment is largely with them, and is giving them encouragement. The Indians, says Mr. Traig, do not purpose to accept the estimate of Captain Mercer's inspectors, and demand that all logs be re-scaled. If the government meets the demand there will be no trouble. If, on the other hand, the logging company of Frazee attempts to take the logs from the reservation without a new scale or estimate, Mr. Trais says there will be serious trouble, as the Indians are determined upon this point, and to this extent are in an ugly mood. They have had several war dances and are preparing feathers. Some of the logs are moving and the situation is fast reaching a critical stage. Captain Mercer had not arrived from Leech Lake when Mr. Traig left Pine Point, and it is impossible to say what he will be able to do to ameliorate present conditions. It is known that some of the Indians are armed and that their preparations to resist the removal of the logs under conditions now existing have been systematic.”

The estimate was that about 60 men with Winchester rifles there stopping any movement of the logs until they could be rescaled. This problem arose from powerful logging companies manipulating employees hired by the Government to protect and regulate the valuable pine lands on the White Earth Reservation. Two of the primary criminals involved were Superintendent Sullivan and a Captain Mercer the man in charge of the inspectors scaling the logs that were cut. The Indian Agent Sutherland resigned and the political wheels in Minneapolis pushed for the appointment of Simon Michelet. Michelet was a close associate of Knute Nelson. Knute Nelson, a Minnesota congressman and latter Governor was one of the most corrupt men related to Indian Affairs in Minnesota. His political support from large business came with his manipulation of Indian rights and land holding. He caused untold hardship for Indian people across the State. His placing Simon Michelet at White Earth only enhanced the trouble for the White Earth people.

With the arrival of Joseph Farr the rescaling of the dead and down pine along with the illegal cutting of live pine trees began. Inspector Farr began work sometime after May11 and by June 8thhe was removed by the Commissioner Jones of Indian Affairs in Washington D.C.

"Inspector Farr was needed in his regular territory in Wisconsin," said Commissioner Jones, "and he was withdrawn from work at White Earth,” Minnesota Journal June 8th 1901.

The next bit of logic used by the Government was to have Captain Mercer select Farr’s replacement. This did not sit well with the Round Lake Ojibwe and moved to bring in an old agreement that the Ojibwe could also select and inspector to rescale the timber cut. Because of newspaper pressure and the armed protest the Bureau had to agree. The information about the problems with the cutting of dead and down policy was also occurring on Leech Lake and Captain Mercer was also operating on that Reservation. All this lead Captain O’Neil to organize and a Congressional involvement into what was going on.

“The work of rescaling was begun in the McDougall lumber camp, and the crew was not quite through with the camp when the telegram ordering a suspension was received. As far as they went, the sealers brought to light an amazing discrimination of the cutting of green pine under the guise of "dead and down" timber. When the work of reseating ceased and the notes of the six different experts were compared and compiled by Mr. Farr it was developed that 1,253,56t5 feet of green standing pine had been illegally cut In the McDougall camp alone.” Minnesota Journal June 8, 1901.

By October 4th Captain O’Neil’s report was finished but he would not reveal his findings. The newspaper was able to gather some information. This information stated.

“It can be stated almost positively that the report of Mr. O'Neil shows even greater frauds than reported by the Farr investigation. The visit of Indian Commissioner Jones to Minnesota last week, In company with Senator Quarles, a member of the committee on Indian affairs of the senate, is thought to have been in connection with the frauds at White Earth. A consultation was held between Special Agent McComas, who was connected with the White Earth investigation; Captain O'Neil, Senator Quarles and the commissioner.” Minnesota Journal October 4th 1901.

The final report was accepted in November stating that some 8,000,000,000 ft of live pine had been fraudulently cut off of the lands at Round Lake.

“The department selected Senator William O'Neil and nine disinterested men to make a rescale of the entire reservation and settle the amount of trespass. Their report sustains my findings says Joseph Farr on every point. On the entire reservation they find 8,580,000 feet, as against 1,260,000 feet as shown inthe report of the agent Mercer. Farr further states at the camp where I made a test scale and did not finish, but found 1,800,000 feet, O'Neil's report shows about 2,200,000 feet, as against 198,000 feet as shown by the representative of the agent Mercer and supported by the contractors.” Minnesota Journal December 28th 1901.

Through the hard work of Skip-in-the-Day and other Ojibwe Leaders and warriors, a Pine Point merchant, and other honest people this fraud was revealed. The Band received the correct payment and corrections in the dead and down pine policy were made. This ended the conflict at Round Lake, but not the conflicts coming at the White Earth Band of Ojibwe.

For the next big manipulation came with trying to “Open up the Reservation.”