Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask at Lensic Performing Arts Center

LaDuke talked about climate change and climate justice in the indigenous peoples’ communities, followed by a conversation with Mililani Trask. This event was part of the In Pursuit of Cultural Freedom lecture series.

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask at Lensic Performing Arts, Santa Fe, NM on February 24, 2016

Winona LaDuke is an Anishinaabekwe (Ojibwe) enrolled member of the Mississippi Band of Anishinaabeg. She is an… Read full bio.

Mililani Trask is a Native Hawaiian attorney and founding mother of the Indigenous Women’s Network. She is widely… Read full bio.

About this Event

Winona LaDuke is an Anishinaabekwe (Ojibwe) enrolled member of the Mississippi Band of Anishinaabeg. She is an indigenous rights activist, an environmentalist, an economist, and a writer, known for her work on tribal land claims and preservation and for sustainable development. LaDuke talked about climate change and climate justice in the indigenous peoples’ communities, followed by a conversation with Mililani Trask.

This event was part of the In Pursuit of Cultural Freedom lecture series.

Audio from this Event

Videos from this Event

Winona LaDuke elsewhere on Lannan.org

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask, 2016, (Events)

Winona LaDuke, (Bios)

Winona LaDuke Lannan Podcast Episodes

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask, 24 February 2016 – Audio

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask, Talk, 24 February 2016 – Video

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask, Conversation, 24 February 2016 – Video

Food Sovereignty: RFP: FOOD SOVEREIGNTY ASSESSMENT GRANTS

First Nations Development Institute (First Nations) is now accepting proposals from Native communities interested in conducting food sovereignty or community food assessments. Under the Native Agriculture and Food Systems Initiative, generously supported by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, First Nations plans to award up to 10 grants of up to $10,000 each to Native communities looking to conduct food assessments and gain a better knowledge and understanding about the historical, current and future state of their local food systems.

First Nations Development Institute (First Nations) is now accepting proposals from Native communities interested in conducting food sovereignty or community food assessments. Under the Native Agriculture and Food Systems Initiative, generously supported by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, First Nations plans to award up to 10 grants of up to $10,000 each to Native communities looking to conduct food assessments and gain a better knowledge and understanding about the historical, current and future state of their local food systems.

Organizations eligible to apply include U.S.-based Native American-controlled nonprofit 501(c)(3), tribes and tribal departments, tribal organizations, or Native American community-based groups with eligible fiscal sponsors committed to increasing healthy food access in rural and reservation-based Native communities and improving the health and well-being of Native American children and families.

http://www.firstnations.org/grantmaking/2016FSA

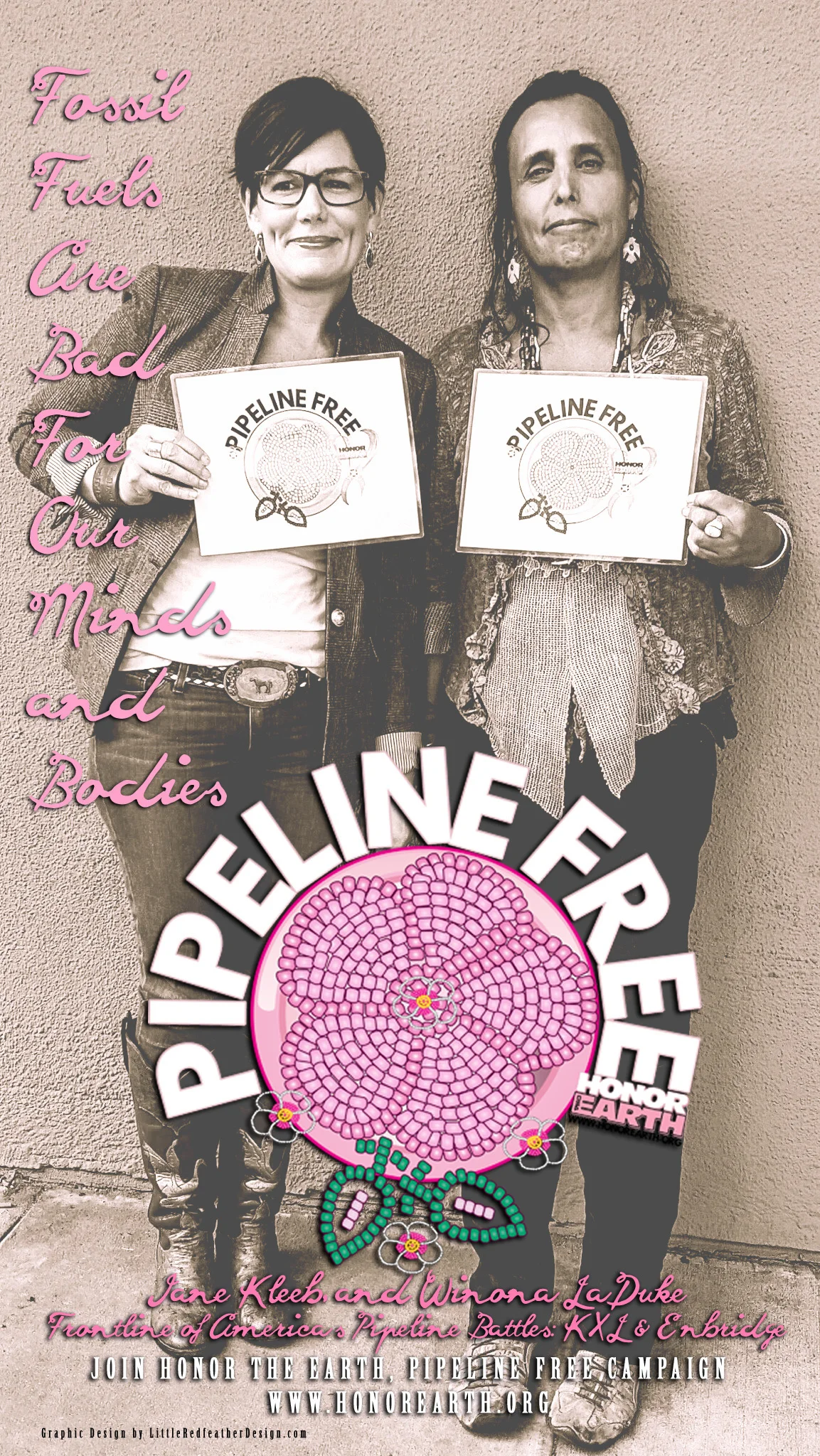

VIDEO: Winona LaDuke (Honor the Earth) takes on Foreign Oil #Enbridge

FOOD + WATER | EARTH - The Battle to Protect our Lands, and Water from Extreme Extractions.

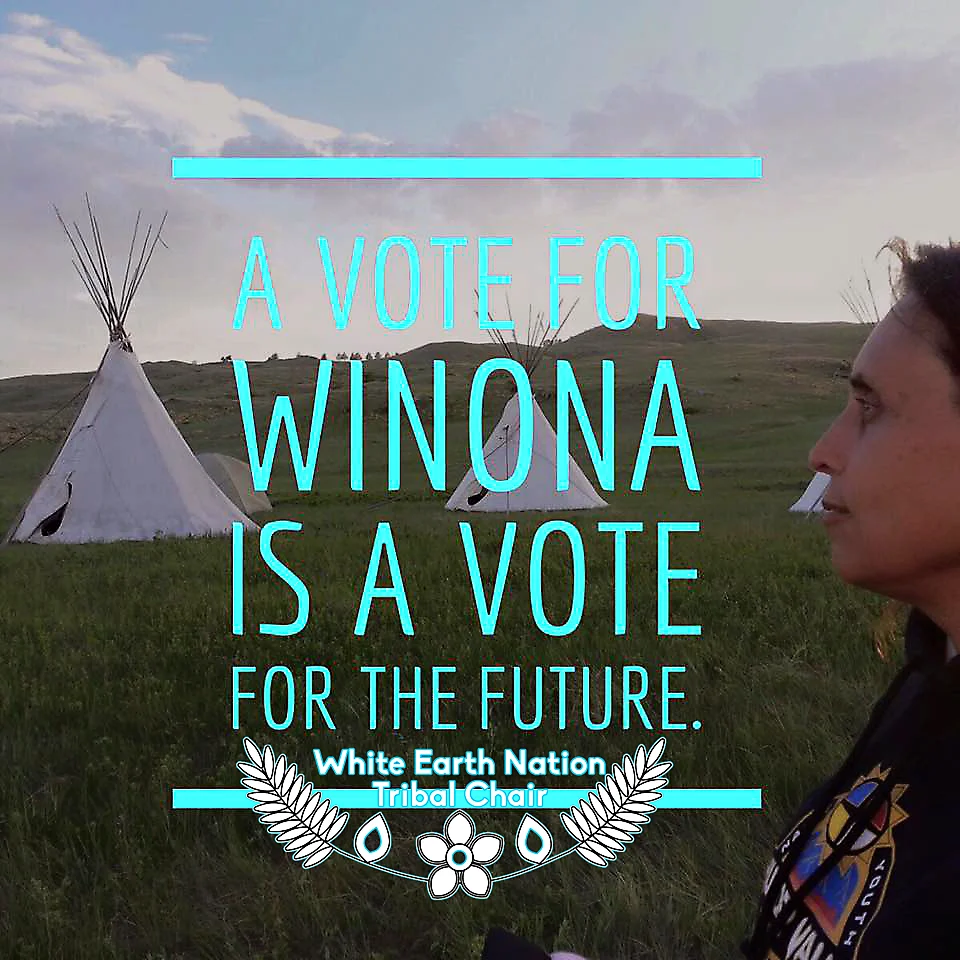

WHY a vote for Winona LaDuke for White Earth Tribal Chair is a Vote for our Future

FOOD + WATER | EARTH - The Battle to Protect our Lands, and Water from Extreme Extractions

WOMAN:: Anshinaabekwe teachings, of course we embody the Earth, but also we’re responsible for the water. The first water that baby is in a woman from the rain to the snow to the rivers (underground aquifers) to that water inside a woman. Those are all the different sacred waters.

WHY a vote for Winona LaDuke for White Earth Tribal Chair is a Vote for our Future:

It is important to come out and VOTE in the upcoming Primary April 5th, 2016. You can request an absentee ballot by writing a note to the:

**Election Board Box 10, Mahnomen Mn 56557

Our people are suffering. We are living in poor conditions because we continue to be robbed; our economy from the cradle to the grave is controlled by others. Today we face many challenges, and future generations will count on us to make a difference. This is our watch. We need to stop the poisons coming in to our community, stop the theft of our economy, land and lives, and protect future generations.

We need to work together.

All of us. There are a number of good people running for this office. The time is now to quit talking badly about each other. That’s how we stay oppressed. Let us put our minds together.

I have worked hard on the environment, on food, on energy and for our families.

- Anishinaabe Akiing fought the White Earth Land Settlement Act.

- The White Earth Land Recovery Project is what I led for 25 years and bought back 1400 acres held by a land trust on the reservation- lands open to tribal members. Native Harvest sells maple syrup, wild rice from the reservation.

- I worked with others to create Niijii Radio, the only independent tribal radio station in Minnesota

- I’ve worked with our tribal members and others to defend our land from genetically engineered wild rice and oil pipelines and to honor the 1855 treaty.

- I have testified at Congress and the Minnesota Legislature, and United Nations, and I can write laws and regulations. And I can work with people.

AGAIN:

A vote for Winona LaDuke for White Earth Tribal Chair is a Vote for our Future: It is important to come out and VOTE in the upcoming Primary April 5th, 2016. You can request an absentee ballot by writing a note to the:

**Election Board Box 10, Mahnomen Mn 56557

Spread the word, download, print and distribute

Article: Can't keep a good woman down: Winona LaDuke

“I became a casualty of the PTSD of the modern Indian Wars,” she writes in the introduction to her forthcoming book The Winona LaDuke Chronicles

"I was taught that cultural expression is the beauty of life and what distinguishes us as humans. … My family has always been interested in people who had courage, who persevered, who kept something valuable of their culture. That's where I come from. Those are the glasses I'm looking through." -- Winona LaDuke

Order at :: www.WinonaLaDuke.com

Q&A: Winona LaDuke - The Nation

Q&A: Winona LaDuke

A conversation with the two-time Green Party vice presidential candidate.

LF: So you decided to ride horseback along the route of the pipeline?

WL: On our reservation, the Enbridge Corporation is applying to nearly double the capacity of its Clipper line to 880,000 barrels per day—that is bigger than Keystone—and they want to build a third pipeline called Sandpiper next to our largest wild rice bed, to carry hydro-fracked oil from the Bakken oil field [in North Dakota] to Superior, Wisconsin. That amount of oil going across northern Minnesota—land of 10,000 lakes—would make this an oil superhighway. I had this dream that we should ride our horses against the current of the oil.

After that, we were invited to ride horse [into Washington]. It was an amazing spiritual experience. Nine teepees on the Mall, saying no to dirty oil and no to climate change, urging President Obama to do the right thing.

Read more: http://www.thenation.com/article/qa-winona-laduke/

How do we grieve the death of a river?

How do we grieve the death of a river? Written by Winona LaDuke

"Our people blocked the road. When the troops arrive, we will face them.”– Ailton Krenak, Krenaki People, Brazil

This eighteen months saw three of the largest mine tailings pond disasters in history. Although they have occurred far from northern Minnesota’s pristine waters, we may want to take heed as we look at a dozen or more mining projects, on top of what is already there, abandoned or otherwise. These stories, like many, do not make headlines. They are in remote communities, far from the media and the din of our cars, cans and lifestyle. Aside from public policy questions, mining safety and economic liability concerns, there is an underlying moral issue we face here:the death of a river. As I interviewed Ailton Krenak, this became apparent.

The people in southeastern Brazilian call the river Waatuh or Grandfather. “We sing to the river, we baptize the children in this river, we eat from this river, the river is our life,” That’s what Ailton Krenak, winner of the Onassis International Prize, and a leader of the Indigenous and forest movement in Brazil, told me as I sat with him and he told me of the mine waste disaster. I wanted to cry. How do you express condolences for a river, for a life, to a man to whom the river is the center of the life of his people? That is a question we must ask ourselves.

November 2015’s Brazilian collapse of two dams at a mine on the Rio Doco River sent a toxic sludge over villages, and changed the geography of a world. The dam collapse cut off drinking water for a quarter of a million people and saturated waterways downstream with dense orange sediment. As the LA Times would report, “Nine people were killed, 19 … listed as missing and 500 people were displaced from their homes when the dams burst.”

The sheer volume of water and mining sludge disgorged by the dams across nearly three hundred miles is staggering: the equivalent of 25,000 Olympic swimming pools or the volume carried by about 187 oil tankers. The Brazilians compare the damage to the BP oil disaster, and the water has moved into the ocean – right into the nesting area for endangered sea turtles, and a delicate ecosystem. The mine, owned by Australian based BHP Billiton, the largest mining company in the world, (and the one which just sold a 60-year-old coal strip mine to the Navajo Nation in 2013) is projecting some clean up.

Renowned Brazilian documentary photographer Sebastiao Salgado, whose foundation has been active in efforts to protect the Doce River, toured the area and submitted a $27 billion clean-up proposal to the government. “Everything died. Now the river is a sterile canal filled with mud,” Salgado told reporters. When the mining company wanted to come back, Ailton Krenak told me, “we blocked the road.”

They didn’t get the memo.

- Read more at: http://americanindiansandfriends.com/news/how-do-we-grieve-the-death-of-a-river-written-by-winona-laduke#sthash.oVTqm8uZ.dpuf

WOMAN ... WINONA LADUKE ABOUT: FOOD + WATER | EARTH

Winona LaDuke, WOMAN, In life, one may not always be sure of their path but for "the signs from above, Honor the Earth repeated, 'trust the process and you'll find what you're looking for.' - We can transition elegantly into a new era, living a good life with the Earth, and water. Let’s be someone that our future generations can depend on, and thank us for.

Photo credit: Keri Pickett | Twitter @KeriPickett

WOMAN

WOMAN is a collection of short films that profile extraordinary women as they push forward the front-lines, around the world. This collection is in development at the moment and will be available to the public in the coming future on a digital platform that allows women and men to explore the feminine experience on earth. We investigate the underlying issues confronting humanity to deepen our understanding of the challenges that bind us all. And through these stories, we aim to shift the prevailing gender paradigm and re-write the inaccurate notions of a woman’s role. This action is a vital avenue toward a more empowering and integrated future.

FOOD + WATER | EARTH

"How do you restore a wild bed?" "Can you tell me how you can do that?" Winona LaDuke during the Enbridge PUC Meeting in McGregor

WINONA LADUKE TAKES ON FOREIGN OIL

"Anshinaabekwe teachings, of course we embody the Earth, but also we’re responsible for the water. The first water that baby is in a woman from the rain to the snow to the rivers (underground aquifers) to that water inside a woman. Those are all the different sacred waters." Winona LaDuke

ENBRIDGE IS CATASTROPHIC:: We have a public policy crisis in the State of Minnesota. We are like the rest of you, we have lived our entire life in the petroleum era. We all use oil. We get that. But we are demanding and expecting a plan, a good plan, is a graceful and elegant transition out of it. Because the fact is what remains in the petroleum era is going to kill us.

Enbridge has not worked on a plan when there is oil leaks and when it would leak in a wild rice lake, even though scientific reports show they have a 57% chance at a catastrophic leak. So Enbridge messaging is that they, “strive for prevention ...,” interesting Enbridge fantasy because prior to a leak the fact is that even though these are areas are delicate aquatic eco system, Enbridge has no training or thought process in their planning to, “restore a wild rice bed,” in the watersheds. Our manoomin, the food that grows on the water, wild rice watershed, and beds are “not,” replaceable. Once they are destroyed, there is no going back to fix this destruction.

We profiled Winona LaDuke as part of our WOMAN collection. She's leading Honor The Earth and her wider community in a battle to stop Canadian oil corporation Enbridge Energy Partners and the Koch Brothers. Saying 'no' to business as usual isn't easy, but clean water and a safe environment are at stake.

After 35 years as a grassroots community organizer: I file to seek the office of Tribal Chair of the White Earth Reservation.

I am asking you to join me. After 35 years as a grassroots community organizer, this week, I file to seek the office of Tribal Chair of the White Earth reservation. The time is now. WhileI intend to continue with our work at Honor the Earth, the need to transition my own community into a fossil fuel reduced, local food future is pressing. This model will be a leading model, not only in Minnesota, and Anishinaabe territory, but also nationally. That is, if I am elected. To do that, I need to start with some seed money; because this campaign will be one of the largest challenges in my life. I am asking you to consider a contribution to the Winona LaDuke Campaign Fund, and to pass the word. Every bit helps, as it will take resources to win this election.

On January 20, as I file, I am challenged to face my own community’s deep need for visionary leadership in the face of huge challenges. Not only are we challenged by two major oil pipelines, but we face ongoing and deep crisis- the crisis of four generations of people being forced into poverty, and the consequences today. My community continues to face health disparities, economic injustices, and major ongoing social trauma. And I will face some opposition from within and without our community.

Dear Trusted Friend,

I am asking you to join me. After 35 years as a grassroots community organizer, this week, I file to seek the office of Tribal Chair of the White Earth reservation. The time is now. While I intend to continue with our work at Honor the Earth, the need to transition my own community into a fossil fuel reduced, local food future is pressing. This model will be a leading model, not only in Minnesota, and Anishinaabe territory, but also nationally. That is, if I am elected. To do that, I need to start with some seed money; because this campaign will be one of the largest challenges in my life. I am asking you to consider a contribution to the Winona LaDuke Campaign Fund, and to pass the word. Every bit helps, as it will take resources to win this election.

On January 20, as I file, I am challenged to face my own community’s deep need for visionary leadership in the face of huge challenges. Not only are we challenged by two major oil pipelines, but we face ongoing and deep crisis- the crisis of four generations of people being forced into poverty, and the consequences today. My community continues to face health disparities, economic injustices, and major ongoing social trauma. And I will face some opposition from within and without our community.

There is no easy answer, but let me share with you some of my thoughts.

- Transition to a restored Anishinaabeg centric economy. This will be an economy of local food, local energy and export of these products at a fair trade rate. My tribe has immense wind potential, the potential to be energy self sufficient, and the potential to be food self sufficient, as well as secure fair trade markets for our heritage foods. We need to have a retail sector of tribal businesses capitalized on this reservation, and those businesses can flourish with the correct tax structure. We need businesses in each community, so people do not have to travel 70 miles a day for a minimum wage job, facing vehicle and childcare challenges. We need access and the ability to protect more of the land in our reservation, including the one third of the reservation held by state, county and federal agencies. We need a just economy.

- Our tribe needs to decriminalize poverty and marijuana. Why is this important? Because being poor means that you have no driver’s license, no insurance; have the ongoing trauma of higher arrests and structural poverty- there are no jobs for those who live here, or return from the prison industrial complex. My tribe has a high level of health impacts and problems related to poverty and the injustice of our health system. My tribe has a high level of drug abuse, and a significant amount of marijuana consumption- many people face time for this, and we need to heal the problems which cause our people to self medicate, and decriminalize marijuana- looking to medical marijuana, hemp and the long term policy of legalizing. We need programs like a Fresh Start, to get rid of fines which plague people and get their licenses back.

- We need to take jurisdiction of energy, the environment, food, and from the cradle to the grave- our own birth and burial ordinances. We need to be hard on polluters and drug dealers- whether in the chemical addition of pollutants to our lands, or the pushing of heroin or meth on our reservation. We need to secure GMO free zones in our territory and continue our work to have wolf sanctuaries. Since the majority of the world’s biodiversity is in Indigenous territories, we need to take the leadership to protect our relatives, whether they have wings, feet, root or paws. We need to be a strong people once again.

- In the time of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, we need to remind the state of Minnesota , and the US federal government that this is not l889, or l930, when our people’s houses were burned to create national wildlife refuges and to take our trees. In this era, Indigenous Peoples must be treated as first class citizens of the world; and our protection of our people, lands, and waters are essential.

I can see where we can go- ji- misawaabandaaming, the future is good for us. But, I will need your help to make this happen. I am setting up a web site, a Kitchen cabinet, and a team of people to work on this election. And I am starting to raise funds for this work.

This has national implications. And international implications- as the issues of Anishinaabe Akiing are pivotal; whether the issues of genetic engineering, or fossil fuel oil pipelines. My opposition will come from not only some in my community; but also a lot of forces who would like to keep our dependency and poverty intact. A vote for me is a vote for the future, Minobimaatisiiwin.

I have lived most of my life in my community; traveled the world, and am home. This is where I want to be, and intend to serve the larger world from this place- omaa akiing. I am asking for you to join me.

Miigwech

Winona LaDuke

January 19, 2016: This is me filing for the office of White Earth tribal chairwoman after thirty five years of community organizing. The Primary is APRIL 5, 2016 ! Get registered. Please. get your ballots and vote for our future Anishinaabeg !

And if you are able to set up a donation to my campaign , that’s a check or money order, it will need to be written to Winona LaDuke Campaign Fund 2016.

Mailing address: Winona LaDuke P.O. Box 268 White Earth, Minnesota 56591

If you are able to make an online contribution: Safe Secure, SquareUpLink

https://squareup.com/store/winona-laduke-for-white-earth-chair

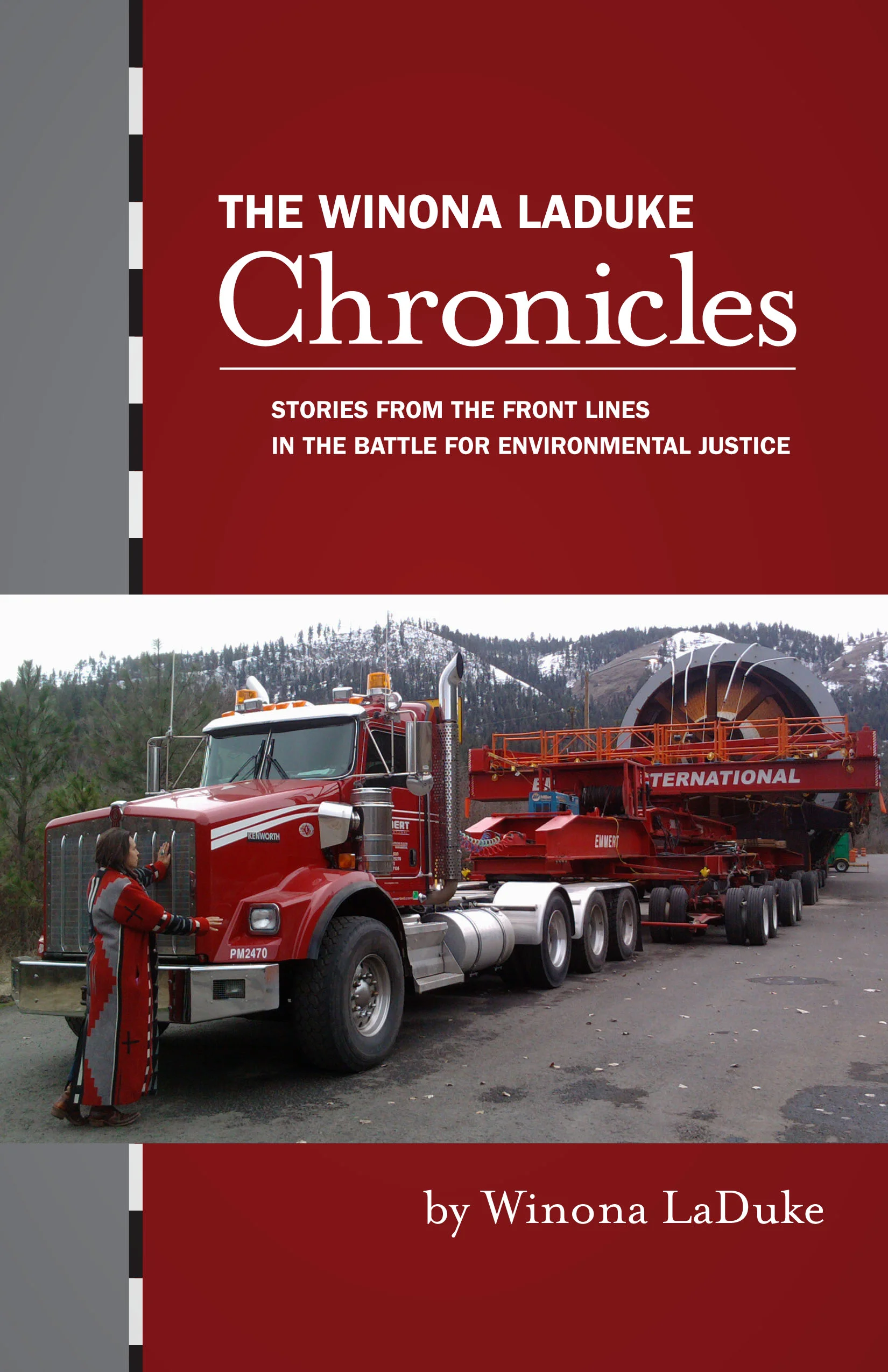

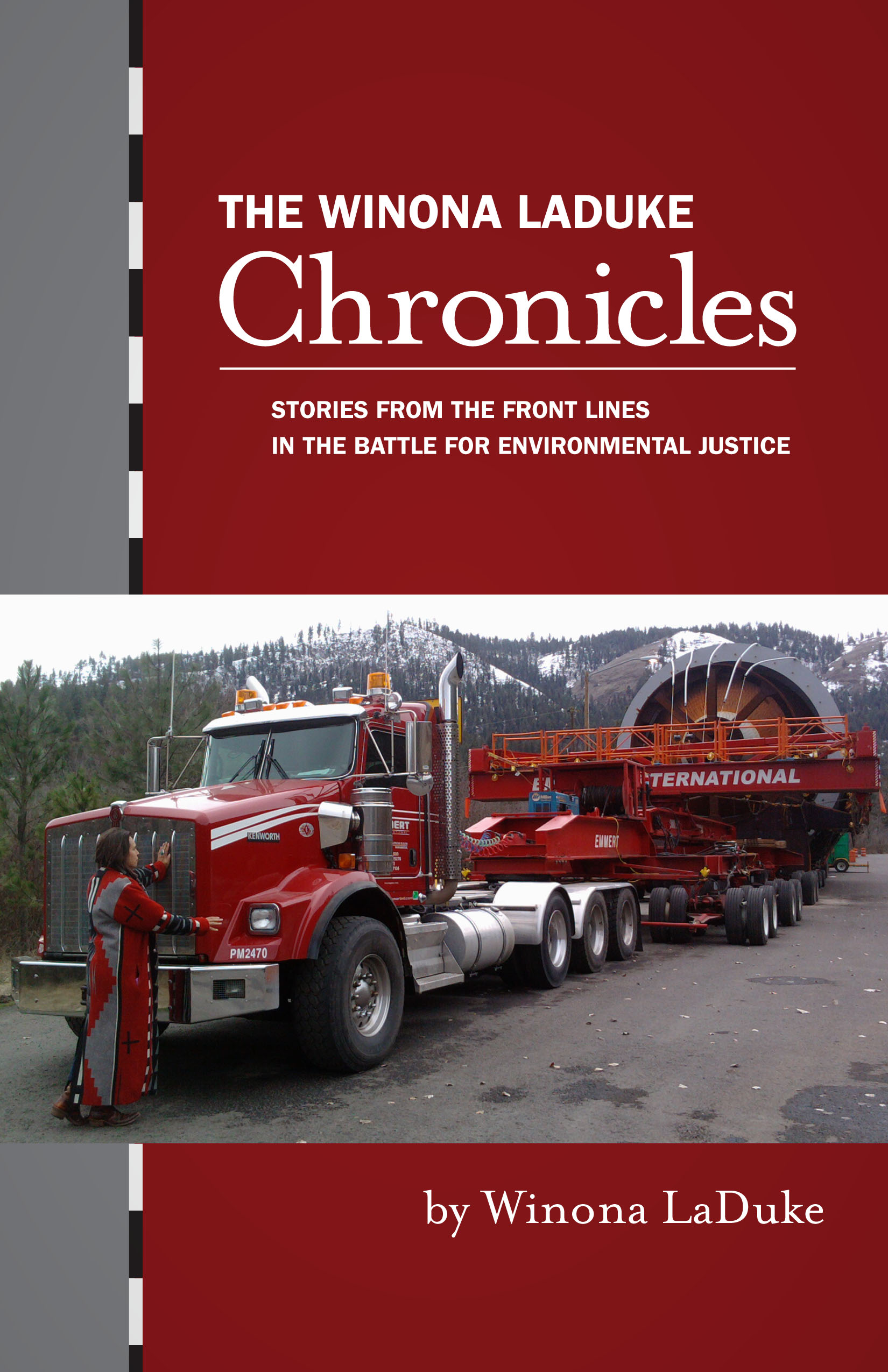

New Book Release The Winona LaDuke Chronicles !

Out: January 2016, Order yours now

“I have lived much of my life on the road. Like my mother and father before me, I travel. For me it is from one tribal nation to another, from University to College, regulatory hearing, court room, to the United Nations; and then home. It is by car, airplane, sometimes by horse or canoe. This is the book of those travels, a privileged life indeed. In this space, people share their stories, or, sometimes, if I am lucky, a story unfolds as I watch; pen in hand.” Winona LaDuke

UPDATE ... The Winona LaDuke Chronicles is now released as of January 2016.

Pre Order Now: The Winona LaDuke Chronicles

Out: January 2016, Pre-Order Yours

“I have lived much of my life on the road. Like my mother and father before me, I travel. For me it is from one tribal nation to another, from University to College, regulatory hearing, court room, to the United Nations; and then home. It is by car, airplane, sometimes by horse or canoe. This is the book of those travels, a privileged life indeed. In this space, people share their stories, or, sometimes, if I am lucky, a story unfolds as I watch; pen in hand.” Winona LaDuke

“Winona LaDuke standing in front of ExxonMobil Heavy Haul truck, near Lolo Hot Springs, Oregon. Truck is stranded on the historic highway 12, Nez Perce territory.”

A two time vice presidential candidate in l996 and 2000, author of five books of non fiction, one children’s’ book and a novel, Chronicles is a major work of current , pressing, and inspirational stories of Indigenous communities- from the Canadian subarctic, to the heart of Dine Bii Kaya, Navajo Nation. Stories range from visits with Desmond Tutu, front line Indigenous leaders, to restored Indigenous farming, and the ability of this society to move from a Tipi to a Tesla. This book tells of the need and the ability to make an elegant transition to a post fossil fuels economy. Long awaited, the book is a labor of love, a tribute to those who have passed on and those yet to arrive.

Quotes from the Book

Winona LaDuke’s, LaDuke Chronicles, comes out this solstice. Long awaited, the book is at once, a travel journal, as she moves from one tribal community, village or gathering to another; and also features well-researched, in depth stories, analysis and tributes. Published by her new Spotted Horse Press publishing company, LaDuke shares much of her life, and the stories which compel her.

From the back cover, “I have lived much of my life on the roadLike my mother and father before me, I travel- from one tribal nation to another, from University to College, regulatory hearing, court room, to the United Nations; and then home. This is the book of those travels, a privileged life indeed. In this space people share their stories, or, just at that moment, a story unfolds as I watch; pen in hand.”

Excerpts:

From Spirit Bear and the Pipeline

“Peter Okimaw walked up to the microphone. He is a middle-aged man from the village of Driftpile, a Cree reserve around 250 miles north of Edmonton. “When I was a kid, I used to drink from those creeks and rivers,” he said. “Now I have to go to Walmart and buy water when I go into the bush by those creeks….”

During this portion of the testimony, the Enbridge representatives made few notes and wrote very slowly.

Okimaw continued: “I had seen the beaver there going crazy. I said to my brother that we wouldn’t go crazy... Sure we’d like to take our children to swim, but where? We have to go to Edmonton to swim in a pool. It’s our traditional land and we should keep it that way. We should save the rest. Once you’ve taken the heart of Mother Nature, then where do we stand? The world will be looking at us in Alberta. They will say, ‘Boy, it was good while it lasted.’”

On Legalization of Marijuana:

“…I am told that 40% of my community smokes the herb. The fact is we’re spending millions of dollars a year importing marijuana from largely unsavory characters onto the reservation, creating a great loss to our tribal economy. This is undeniable in every reservation. I haven’t done complete studies, but in order to buy marijuana from dealers elsewhere, conservative estimates indicate that $60,000 a week is draining from my own reservation, White Earth. With a little math, it looks like around $3 million annually heads to the drug lords, or maybe just the Nancy Botwin of theWeeds series.

From Tipi to a Tesla- Me and Emma:

“…I would like to drive a couple of cars in the next few years. I would like to drive a Jaguar—not own one, just drive one—across the Golden Gate Bridge. Maybe navy blue, or slate grey. And maybe a real old school car, too, like an old Chevy. A rounded-edges one. No sharp fins.

Why would I like to do this? Because—in their own way—they are works of art to me, perhaps to all of us, beautiful works of art created in a fossil fuel era. And that era will be over soon, because it is time…. I just want to see an elegant transition, not a crashing-my-way-out-of-the-fossil-fuel-era transition of climate change and poison.

The reason why I know that the fossil fuel era in cars will end is a simple energy inefficiency problem. Of the six gallons of gas you put into the car, only about one gallon actually moves the car forward….

Emma Lockridge is holding a sign that says: “Marathon Buy my House”. She is wearing a shirt that says “Blood Oil “on it, with a picture of the Marathon Refinery. Then she says, “We have a tar sands refinery in our community and it is just horrific... We are (a) sick community. We have tried to get them to buy us out. They keep poisoning us. And we cannot get them to buy our houses.”

On the Violence Against Women Act ( Jancita Eagle Deer) “We cannot vote for an amendment…that basically strips the rights of Native American women and treats them like second-class citizens. Nor can we just go silent on what is an epidemic problem in our country.” – Senator Maria Cantwell

On Idle No More and Canadian Colonialism:

“ There is some money flowing in, that’s sure. A 2010 report from DeBeers states that payments to eight communities associated with its two mines in Canada totaled $5,231,000 that year. Forbes Magazine reports record diamond sales by the world’s largest diamond company “…increased 33 percent, year-over-year, to $3.5 billion…”

As the Canadian Mining Watch group notes: “Whatever Attawapiskat’s share of that $5-million is, given the chronic under-funding of the community, the need for expensive responses to deal with recurring crises, including one that DeBeers themselves may have precipitated by overloading the community’s sewage system, it’s not surprising that the community hasn’t been able to translate its…income into improvements in physical infrastructure.”

Last year, Attawapiskat drew international attention when many families in the Cree community were living in tents in the dead of winter. The neighboring Kashachewan Village is in similar disarray. They have been boiling and importing water. The village almost had a complete evacuation due to health conditions, including a scabies and impetigo epidemic…”

“...In the North American first world, tribal communities and first nations struggle just to survive. In our resilience and beauty, these stories are inspired,” LaDuke explains.

A two time vice presidential candidate in l996 an 2000, author of five books of non fiction, one children’s’ book and a novel, Chronicles is a major work of current, pressing and inspirational stories of Indigenous communities- from the Canadian subarctic, to the heart of Dine Bii Kaya, Navajo Nation. Stories range from visits with Desmond Tutu, front line Indige A two time vice presidential candidate in l996 and 2000, author of five books of non fiction, one children’s’ book and a novel, Chronicles is a major work of current, pressing and inspirational stories of Indigenous communities- from the Canadian subarctic, to the heart of Dine Bii Kaya, Navajo Nation. Stories range from visits with Desmond Tutu, front line Indigenous leaders, torestored Indigenous farming, and the ability of this society to move from a Tipi to a Tesla. This book tells of the need and the ability to make an elegant transition to a post fossil fuels economy. Long awaited, the book is a labor of love, a tribute to those who have passed on and those yet to arrive.

"Chronicles is a book literally risen from the ashes—beginning in 2008 after her home burned to the ground—and collectively is an accounting of Winona LaDuke's personal path of recovery, finding strength and resilience in the writing itself as well as in her work." Sean Cruz

Pre-order today! $23.00 post paid (US).

Retail: Contact us for wholesale and University prices.

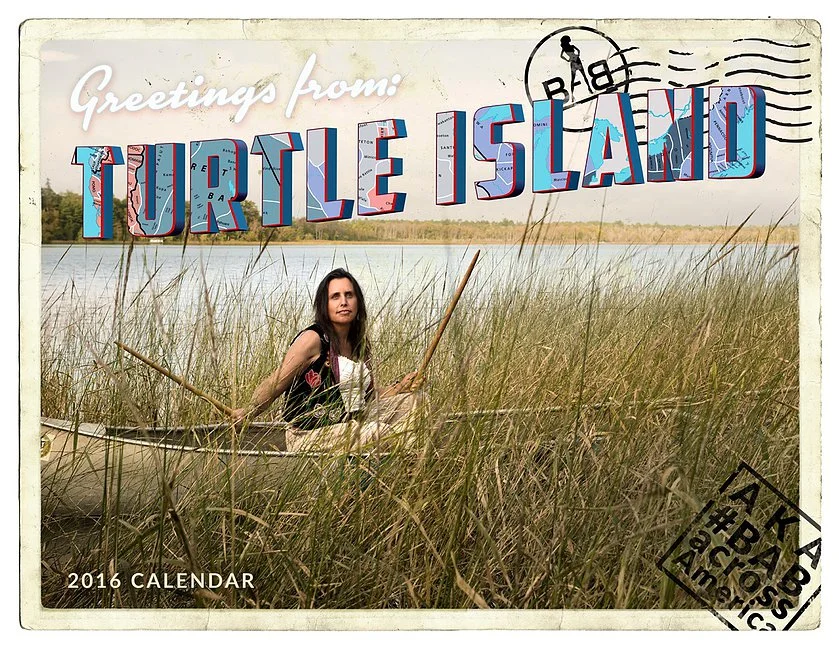

2016 Babes Against Biotech Calendars featuring Winona LaDuke

2016 Babes Against Biotech Calendars Pre-sale Now!

Support our stand for renewable, ecological agriculture, sustainable food systems, indigenous rights and social justice. Live your #BABlife every day in 2016!

We are very grateful to announce our 2016 Cover Role Model Winona LaDuke, internationally renowned activist, environmentalist, economist, and writer, known for her work with indigenous rights, land protection, and sustainable development. A former Green Party Vice President candidate, Winona is continuing to lead today by setting an example for all generations of devotion to the greatest good and human, indigenous and environmental justice for all.

Support our stand for renewable, ecological agriculture, sustainable food systems, indigenous rights and social justice. Live your #BABlife every day in 2016!

We are very grateful to announce our 2016 Cover Role Model Winona LaDuke, internationally renowned activist, environmentalist, economist, and writer, known for her work with indigenous rights, land protection, and sustainable development. A former Green Party Vice President candidate, Winona is continuing to lead today by setting an example for all generations of devotion to the greatest good and human, indigenous and environmental justice for all.

An Interview with Winona LaDuke by Yes! Magazine

An Interview with Winona LaDuke

On Wild Rice, Wind Power, Thunder Beings, Self-reliance, and our Covenant with the Creator

Sarah van Gelder posted Jun 17, 2008

Winona LaDuke and her son, Gwekaanimad, during a visit to the Suquamish Tribe’s Clearwater Resort in Washington state. Winona LaDuke is an Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) and the executive director of Honor the Earth, and founding director of White Earth Land Recovery Project. Photo by Harley Soltes for YES! Magazine

Sarah van Gelder: Could you tell me about your background?

Winona LaDuke: My father was Anishinaabe and my mother was a first-generation Russian/Polish Jew from New York. Both were involved with social movements—the Native American movement, farmworkers’ movement, poor people’s campaign, and the environmental movement.

I’m Bear Clan from the White Earth reservation, which is located between Bemidji and Fargo. My parents met because my dad was selling wild rice. I am part of a wild ricing culture. We are not rich in money, but we are wealthy in rice and other traditional foods. Sun Bear was my father’s name, and he used to have a saying: “I don’t want to hear your philosophy if it doesn’t grow corn.”

Sarah: You have focused much of your work on food and energy. What is your approach to these two basics?

Winona: Well first, we have to relocalize our economies. That doesn’t mean no imports and exports. But whether it’s food or energy, we’ve got to cut consumption; we’ve got to be responsible and efficient about what we use; and we’ve got to produce energy and food locally as much as you can.

There’s a phrase in Ojibwe, ji-misawaanvaming, which means something like positive window shopping for your future. We need to ask what our community is going to look like 50 or 100 years from now.

I’ve worked in my own community since 1981. We tried waiting for the federal and state government to take care of things, and if we had not taken action, we would still be waiting and I’d probably have a big ulcer from complaining, or kvetching as we say in Yiddish. We decided instead to put our hearts and minds together. We may not be the smartest, or the best looking, or the richest, but we are the people who live here. We decided we wanted to make decisions about the future of our community.

Sarah: What do your teachings tell you about creating that future?

Winona: We have a lot of teachings and language about how a people can live a thousand years in the same place and not destroy things. The phrase anishinaabe akiing, for example, means the land to which the people belong. It’s not the same thing as private property or even common property. It has to do with a relationship that a people has to a place—a relationship that reaffirms the sacredness of that place.

All our places are named. Near Thunder Bay, Ontario, is “The Place Where the Thunder Beings Rested on their Way from West to East.” We go there to do vision quests, to reaffirm our relationship with that power, and to offer our gifts to the thunder beings and the part they played in our creation. That place, and the places where our people stopped on their migration—all these places are named—and they have a resonance with us.

In all our teachings we understand that all the creatures are our relatives, whether they are muskrats or cranes—whether they have fins or wings or paws or feet. And in our covenant with the Creator, we understand that it is not about managing their behavior—it’s about managing ours, because we’re the ones who cause extinction of species. We’re the youngest species, and we don’t necessarily have the most smarts. We’ve bungled up along the way, and we acknowledge these mistakes in our stories and in our history as Indian people. The question is whether you have the humility and the commitment to get some learning out of these experiences.

Winona LaDuke. Photo by Harley Soltes for YES! Magazine

Sarah: What happens when this land ethic and this humility bump up against the dominant culture?

Winona: Ninety percent of the land on our reservation is held by non-Indian interests. We had the misfortune of having a neighbor who lived just to the south of us named Frederick Weyerhaeuser. We had fine white pine on our reservation, and he built his empire off of the land of the Ojibwe people in northern Minnesota.

And that is how some get rich and some get poor. It’s important to remember that most of these guys did not get rich by spinning flax into gold. They took someone else’s land, and they took someone else’s wealth.

That place known as The Place Where the Thunder Beings Rest isn’t called that now. It’s now called Mt. McKay. I don’t have a problem with Mr. McKay, but I do have a problem with this practice of naming large mountains after small men. How could we name something as immortal as a mountain after something as mortal as a human?

This could be fixed. Just look at Ayers Rock in Australia. It’s called Uluru now, because that’s its traditional name. Mt. McKinley in Alaska is now called Denali. The country of Rhodesia is now called Zimbabwe. It’s not disastrous to rename.

Sarah: Can you tell me about how wild rice is harvested?

Winona: We go up on the lake and we put our asemaa, our tobacco, on it. My son is my ricing partner, and we canoe through our rice beds. I used to push him, but he got too big, so now he pushes me out there, and I knock rice into the canoe with two sticks.

The rice grows on our lakes and rivers—some is fat and some skinny, some short, some tall. Some grows in muddy waters, some looks like a bottle brush, and some looks all punked out. That’s called biodiversity. It means not all the rice ripens at once. Some gets knocked off by wind. Some gets a blight, some doesn’t get a blight. The Irish potato famine should have taught us that agricultural monoculture is dangerous—but so is a social monoculture (or you could say, mall-culture).

The anthropologists used to come out and watch us manoominike—harvest the rice. After we rice in the morning, we bring our rice in and let it dry. We parch it over a fire, and we dance on it to get the hulls off, and then winnow it in a basket. We pretty much do the same thing today using wood fires as we’ve always done—we’re an intermediate technology people.

Ojibwe is a language of 8,000 verbs. The word for “work” is a strange construct for us. It doesn’t mean we aren’t a hard-working people, but in our language, the word is anokii, which means that whether you are fishing or weaving a basket, what you are doing is living—which is not the same thing as being paid a wage to do something.

After the harvest, we have a big feast, and we dance and tell stories. The anthropologists watched us, and they didn’t like that. They said we would never become civilized because we enjoyed our harvest too much. We did too much dancing, too much singing.

When you no longer enjoy your relationship to your food, to your plant relatives, to the harvest, to the dancing and singing—when you end up with a harvest that has no relationships or joy, I think that must be the mark of civilization and industrialized agriculture.

Sarah: What is the foundation for your economy? Do you sell your rice?

Winona: We sell our rice through Native Harvest. But for us, eating the rice is more valuable than selling it. Ensuring that our people have enough rice is what we’re after.

In our community, we don’t have a lot of wealthy people, but we have a lot of drums. We have a lot of songs. We have great maple syrup, harvested by hand and by horse, and boiled by wood. We are able to access the medicine chest of the Ojibwes. We have knowledge that is 10,000 years old. And we have the wealth of our relations to each other and to the natural world.

In our community, the stature of a human being is not associated with how stingy you are and how much you have in your bank account. It’s how much you give away, how generous you are.

It took the University of Minnesota about 40 years to figure out how to domesticate wild rice and cultivate it in rice paddies using chemicals and fertilizers, regulated so it could be harvested with a combine. They called it progress, declared it the state grain of Minnesota, and it took just a couple of years before Uncle Ben’s and the others took it over. Today, three quarters of all wild rice on the grocery shelf comes from giant rice paddies in California. No Ojibwe in sight.

Two Indians in a canoe can’t compete with a guy on a combine. One of my elders, Margaret Smith, and I went out to the lakeside because rice buyers were there trying to force the price they’d pay Indian people for rice down to 50 cents a pound. We said we’re going to pay a buck a pound. Margaret’s a good bluffer. They didn’t know how much money we had.

In 1986 we started fighting their right to call it “wild rice” because we think wild should mean something. In Minnesota you have to label rice as cultivated or wild, but in California or Oregon you can still sell cultivated rice as “wild” rice.

Our worst fears came true when the University of Minnesota cracked the DNA sequence of wild rice in the year 2000. They have not genetically engineered wild rice, but they want to reserve the right to do so. Our people do not believe that our sacred food should be genetically engineered, so we have been battling them for seven years.

Our foods are very much threatened, and this is an international issue for indigenous people.

After the harvest, we have a big feast, and we dance and tell stories. The anthropologists watched us, and they didn’t like that. They said we would never become civilized because we enjoyed our harvest too much.

Sarah: Besides protecting wild rice, what are you doing to bring back traditional foods?

Winona: We are growing more of our own food. About seven years ago, we got a handful of Bear Island flint corn from a seed bank and now we have about five acres of it. The corn is higher in amino acids, antioxidants, and fiber than anything we can buy in the store.

The traditional varieties of food that we grew as indigenous peoples—before they industrialized them and bred out much of the nutritional value—are the best answer to our diabetes. A third of our population is diabetic. We give elders and diabetic families traditional foods every month: buffalo meat, wild rice, hominy.

My 8-year-old, Gwekaanimad, and I started a pilot project with theschool lunch program after I saw that they were eating pre-packaged food from

Sodexho, Sysco, and Food Services of America. We try to give our school kids a buffalo a month and also some deer meat, some local pork, and local turkeys. We started growing and raising our own. It’s just a start. We had to de-colonize our kids, too, because they got used to thinking that their food was that other stuff.

We plowed 150 gardens last year on our reservation. I’m a big proponent of gardens, not lawns. It turns out in most reservation housing projects you can’t grow food. That spot in front of your house is where you park your car, or your dogs will trample it, or your cousin will drive over it. So we’re putting two-foot-tall grow boxes up there, and you can grow a lot of vegetables in them.

Our goal is to produce enough food for a thousand families in five years. And these foods we are growing in anishinaabe akiing are not addicted to petroleum, and they don’t require irrigation or all those inputs. These strong plant relatives just require songs and care for the soil. And in a time of climate destabilization, that is what you want to be growing. You don’t want to be guessing with some hybrid.

Sarah: What about relocalizing energy?

Winona: I’ve worked on energy issues pretty much my whole life. I’ve worked in Indian communities that are facing the biggest corporations in the world, and I’ve seen the effect of those corporations on land, people, and dignity.

Now, after 30 years fighting coal mines and uranium mines, to see the Bush Administration and Stewart Brand saying “nuclear power is the answer to climate change” I just feel that it’s time to move out of the box and into the next energy economy.

So now wind developers are coming into Indian country, which, it turns out, is rich with renewable potential.

Bob Gough from the Intertribal Council on Utility Policy says you’re either going to be “at the table” or you’re going to be “on the menu.” I want to see our Indian communities produce wind power on our own terms and own it. I want to see our young people benefit from it and train to be part of the next energy economy. We are a rural part of the Jobs not Jails movement that Van Jones and Majora Carter are leading in urban areas.

They say Native people in this country have the potential to produce one third of the present installed U.S. electrical capacity. When I first proposed a windmill on my reservation, members of the tribal council looked at me like I was nuts. But now one of my guys made me laugh, he said, “You know Winona, we used to think that you were crazy, but now we see that you were right. Someone had to stick their neck out!”

My tribe is putting up a 750 kilowatt wind turbine to power our tribal office building. Our organization put up a 250 kilowatt turbine. A tribe four lakes away has a lot of money, but not much wind; they asked us to site a two megawatt turbine for them on our reservation.

We are putting solar heating panels on the south side of our elders’ housing. It’s very simple technology; when the sun heats the panel up to about 90 degrees, the thermostat cranks on the blower fan, and blows hot air into your house. It works for us because even when it’s 20 below zero, the sun shines.

But we start with energy efficiency. I don’t support creating energy to feed an addict unless you deal with the addiction.

Sarah: What gives you hope to keep on with this work?

Winona: Life is good. We’ve been blessed with food that grows on water (wild rice) and sugar that comes from trees.

We’re technically one of the poorest counties in the state of Minnesota. My theory is, if we can do it, anybody can do it. It’s up to us—we’re making the future. If we’re waiting for somebody else to grow those gardens for us, well, we’re not high on their priority list. We have a shot at doing the right thing. So mino bimaadiziiwin (the good life), that’s the future we’re trying to create in our community.

Sarah van Gelder interviewed Winona LaDuke as part of A Just Foreign Policy, the Summer 2008 issue of YES! Magazine. Sarah is the Executive Editor of YES! Magazine.

Winona LaDuke on The Colbert Report

WINONA LADUKE

06/12/2008 VIEWS: 60,036