Winona LaDuke + Naomi Klein: Land Rights and Climate Change

Naomi Klein, the award-winning journalist, author, and Rutgers Gloria Steinem Chair of Media, Culture, and Feminist Studies, joins in conversation with rural development economist and Indigenous land rights activist Winona LaDuke. Drawing from their experience on the frontlines of the struggle for a more just and sustainable world, they delve into a host of related questions:

What is the best model of economic development?

What can we learn from First Nations about how to measure wealth, poverty, and equity?

What should the role of government be in confronting the causes of climate change?

What are the implications of the global frameworks proposed for decarbonization and forest protection?

What are the common themes and insights in the stories that women are voicing from the frontlines?

Winona LaDuke + Naomi Klein: Land Rights and Climate Change

As climate change is beginning to alter the planet before our eyes, two internationally recognized activists come together at the Rubin to discuss the economics associated with climate change, the role of First Nations in the climate movement, and the connections between violence against women and violence against the land. Naomi Klein, the award-winning journalist, author, and Rutgers Gloria Steinem Chair of Media, Culture, and Feminist Studies, joins in conversation with rural development economist and Indigenous land rights activist Winona LaDuke. Drawing from their experience on the frontlines of the struggle for a more just and sustainable world, they delve into a host of related questions: What is the best model of economic development? What can we learn from First Nations about how to measure wealth, poverty, and equity? What should the role of government be in confronting the causes of climate change? What are the implications of the global frameworks proposed for decarbonization and forest protection? What are the common themes and insights in the stories that women are voicing from the frontlines?

‘Everyone comes here with a backstory’ By Arlyssa Becenti

‘Everyone comes here with a backstory’ - NTU commencement spotlights Winona LaDuke, John Pinto

By Arlyssa Becenti | May 23, 2019

Image: Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero

A Navajo Technical University graduate takes a selfie with guest speaker Winona LaDuke at the university's commencement last Friday.

TU commencement spotlights Winona LaDuke, John Pinto

Navajo Times | Donovan Quintero

A Navajo Technical University graduate takes a selfie with guest speaker Winona LaDuke at the university's commencement last Friday.

Kyleigh Largo clasped tightly to her dad, Corwin Largo, who had just received his bachelor’s in industrial engineering with a minor in mathematics from Navajo Technical University.

“I really wanted my daughter to say that, ‘My dad is an engineer,’ said Largo. “That was my motivation to finish this degree. It was a challenge. I just want her to live comfortably. I want to take care of her and hope she follows in my footsteps.”

Largo received his degree on Friday, along with 23 others who received their undergraduate degrees, 84 who received certificates, 71 who received associates and 27 GED recipients.

Candid about how a tribal college wasn’t his first choice, Largo said that changed when he actually got on campus and began taking the classes.

“When you start applying for colleges you don’t think of coming to a tribal college until you are on campus,” said Largo. “Everyone comes here with a backstory. I’m glad I came here and finished here.”

Not a stranger to the Crownpoint area, commencement speaker Winona LaDuke gave an inspirational commencement speech.

She told the audience that she “owes a lot of debt” to the Navajo people, because while a student studying energy economics at Harvard University, she spent a lot of time researching uranium and coal strip mining on Navajo.

“I spent a lot of time here with people who changed my life,” said LaDuke. “I came here as a young woman and it taught me a lot. I saw the massive amount of exploitation, which occurred in our territories. From my experience here I learned more the value of water than I’ve learned anywhere else. Learned the value of what is right.”

Natives taking back their knowledge and education, LaDuke said, was a prophecy that was expressed.

The prophet she refers to came from the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, where she is from, and foresaw the arrival of white people, the disappearance of Natives as well as their “things,” and the establishment of residential schools.

“They talked about these people who would be born,” said LaDuke. “These new people would find the things that was taken. They would go and reclaim things … in that we would remember who we are. I think that is the age of tribal colleges. When we, as Native people, take back the control of our education and knowledge systems.”

Graduating with her industrial engineering degree, Adriane Tenequer said NTU was close to home and it offered her numerous opportunities to work for various industries. She had worked with the Boeing Company, and now that she has graduated she will be heading to Alabama to work with Jacobs Technology at Marshall Space Center.

As a mother of two, she said her schedule revolves around her children, so with the help of her family and the close proximity of NTU, she was able to pursue her engineering passion.

“Engineering is something I’ve always wanted to do,” said Tenequer. “At one point I want to have my own business here so I can fulfill employment in this area. I’ve had a lot of opportunities through NTU.”

NTU President Elmer Guy spoke on the school’s 40-year evolution, from the Navajo Skills Center to Crownpoint Institute of Technology to Navajo Technical College and then Navajo Technical University.

He boasted that the university was ranked by bestcolleges.com the No. 3 college in New Mexico, outranking the University of New Mexico.

In its 40th year, Guy was proud to announce the school would be presenting its first honorary doctorate degree to New Mexico State Sen. John Pinto.

Pinto, 94, was a Navajo Code Talker and has served in the senate for the 3rd District since 1977.

“As a senator and a code talker he has always pushed Navajo Technical University for funding,” said Guy. “We are honoring that past that has made the university what it is today. In that context, we are honoring Senator Pinto with a honorary doctorate.”

Guy told the graduates saying that he hopes they continue with their education. An inspirational example of this message was AIHEC’s student of the year, Darrick D. Lee, who received his bachelor’s in electrical engineering.

In an emotional message to his fellow graduates, Lee, from Shiprock, said he slept in his truck and camped out at a friend’s house in order to commute to school.

“Whether you plan to go straight to work right after you graduate or continuing your education, just know it’s going to take a lot of hard work,” said Lee. “Everyone has a right to be here to get an education. You are privileged to be here. You are now responsible to use what you learned from here.”

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the United States paperback featuring Foreword by Winona LaDuke

Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the United States

Restoring Cultural Knowledge, Protecting Environments, and Regaining Health

Edited by Devon A. Mihesuah, Elizabeth Hoover, Foreword by Winona LaDuke

Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the United States

Restoring Cultural Knowledge, Protecting Environments, and Regaining Health

Edited by Devon A. Mihesuah, Elizabeth Hoover, Foreword by Winona LaDuke

Centuries of colonization and other factors have disrupted indigenous communities’ ability to control their own food systems. This volume explores the meaning and importance of food sovereignty for Native peoples in the United States, and asks whether and how it might be achieved and sustained.

Unprecedented in its focus and scope, this collection addresses nearly every aspect of indigenous food sovereignty, from revitalizing ancestral gardens and traditional ways of hunting, gathering, and seed saving to the difficult realities of racism, treaty abrogation, tribal sociopolitical factionalism, and the entrenched beliefs that processed foods are superior to traditional tribal fare. The contributors include scholar-activists in the fields of ethnobotany, history, anthropology, nutrition, insect ecology, biology, marine environmentalism, and federal Indian law, as well as indigenous seed savers and keepers, cooks, farmers, spearfishers, and community activists. After identifying the challenges involved in revitalizing and maintaining traditional food systems, these writers offer advice and encouragement to those concerned about tribal health, environmental destruction, loss of species habitat, and governmental food control.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Devon A. Mihesuah, a member of the Choctaw Nation, is Cora Lee Beers Price Professor in International Cultural Understanding at the University of Kansas. She has served as Editor of the American Indian Quarterly and is the author of numerous award-winning books, including Choctaw Crime and Punishment, 1884–1887; American Indigenous Women: Decolonization, Empowerment, Activism; Recovering Our Ancestors' Gardens: Indigenous Recipes and Guide to Diet and Fitness; American Indians: Stereotypes and Realities; and Cultivating the Rosebuds: The Education of Women at the Cherokee Female Seminary, 1851–1909.

Elizabeth Hoover, Manning Associate Professor of American Studies at Brown University, is the author of articles about food sovereignty, environmental health, and environmental reproductive justice, as well as the book The River Is in Us: Fighting Toxics in a Mohawk Community. She is a board member of the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance and of the Slow Food Turtle Island regional association and has worked with the Mohawk organization Kanenhi:io Ionkwaienthon:hakie.

Winona LaDuke, an Anishinaabe writer and economist from the White Earth reservation in Minnesota, is Executive Director of Honor the Earth, a national Native advocacy and environmental organization, and the author of numerous articles and books.

REVIEWS & PRAISE

“Return and recovery is very much at the heart of this volume. Indigenous food sovereignty argues for rooted and collective continuance. More than about development and conservation—or resilience even—it is about sacredness and intimacy, health and sovereignty, food and identity; and it comes from a place deep within.”—Virginia D. Nazarea, author of Heirloom Seeds and Their Keepers: Marginality and Memory in the Conservation of Biological Diversity

“The collective wisdom of Turtle Island’s indigenous peoples offered in Indigenous Food Sovereignty charts a course for decolonization and liberation—and a vision for a better food system and a just society.”—Eric Holt-Giménez, author of A Foodie’s Guide to Capitalism

“This thoughtfully curated collection of essays gives food scholars a vital window on the gorgeous and fierce resilience of indigenous food systems and the activists who work to preserve them against steep odds. It will shape the way we think about indigenous food systems for years to come.”—Amy Trauger, author of We Want to Live: Making Political Space for Food Sovereignty

BOOK INFORMATION

17 B&W ILLUS., 1 CHART, 4 TABLES

390 PAGES

PAPERBACK 978-0-8061-6321-5

PUBLISHED AUGUST 2019

Book Review of Winona LaDuke: "A Bard for Environmental Justice"

Winona LaDuke Chronicles: A Bard for Environmental Justice "LaDuke is one of the great overlooked orators of our time, and she brings this prowess to every page."

Written by: Georgianne Nienaber

Writer and author

Winona LaDuke’s latest book reads like a prayer. These are holy words— inspirational stories taken straight from the heart of indigenous communities throughout the world. The Winona LaDuke Chronicles: Stories From the Front Lines in the Battle for Environmental Justice is lyrical, instructional, and infused with wry humor when the weight of the message becomes unbearable. LaDuke provides a roadmap through tribal nations’ belief systems; offering a spiritual compass and invaluable insight into the relationship of prophesy to the realities of climate change, economic collapse, food scarcity and basic human rights. As it happens, prophesy does come true and redemption is possible despite this encyclopedia of environmental and spiritual insults.

Are we hell-bent on embracing environmental calamity or is atonement and redemption possible through the lessons offered by indigenous belief systems? How fascinating to learn that corn has a history, that seeds have a profound spiritual meaning, and that plants have a sacred relationship with humans. Provide the environment in which food will flourish and there will be no need for genetic crop engineering.

LaDuke is one of the great overlooked orators of our time, and she brings this prowess to every page.

Her standard biography is well known. A two time Green Party vice-presidential candidate, LaDuke has 40 years of activism behind her. A graduate of Harvard University, LaDuke is an Anishinaabekwe (Ojibwe) enrolled member of the Mississippi Band of Anishinaabeg. In the preface to Chronicles, she offers testimony to all that life teaches. As for those two losing vice-presidential campaigns, in the essay, “Recovering from the Drama of Elections,” LaDuke calls out Republican Speaker of the House Paul Ryan and offers valuable and obvious advice. “People want to be heard.” American politics should be defined by diversity rather than establishment money and corporations afforded the status of personhood.

The metaphors of fire and resurrection infuse the story telling.

“I have now more winters behind me than before me. It has been a grand journey. I am grateful for the many miles, rivers, and places and people of beauty,” LaDuke writes.

It was after the loss of her home to fire in the early days of a bleak 2008 winter; a loss that included books, a lifetime of memorabilia, and sacred objects, that the orator and writer temporarily lost her voice. LaDuke says she could not write, could not sleep and could barely speak. Memory became tenuous as she struggled with the even more profound losses of her father, the father of her children, and her sister. She equates the rock bottom feeling of PTSD with being “a casualty of the modern Indian Wars.” She had lost her loves, her heart and some of her closest friends. But “after the burn” indigenous people know that the fields, the forests and the prairies rebound with new growth. LaDuke found this growth in the writing and the story telling. Now a self-described “modern day bard,” she travels across the land, sharing stories from other lands and writing them down along the way.

These are her chronicles, at once universal and very personal.

In these days of the great Canadian fire that has devastated Fort McMurray, it is a stunning coincidence that in the early pages of Chronicles, LaDuke tells the story of a 2014 meeting with Archbishop Desmond Tutu there. The town, which has endured much suffering in the current news cycles, is the booming center of the Alberta Tar Sands projects. It is also the ancestral home of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation. Tutu was there to speak about climate change and global warming. Media coverage criticized Tutu as being misinformed. Tutu warned that pipelines and oil contribute to the devastation of First Nation lands and livelihood and that the resulting climate change would be devastating.

Scientists attribute the Alberta firestorms to climate change. A prophecy fulfilled?

The essay “My Recommended Daily Allowance of Radiation,” slams the North Dakota Department of Health for approving the increase of radioactive materials scuttled in landfills by a factor of 10 or 1000 percent. (from 5 pico curies per liter to 50) It seems the fracking industry was dumping 27 tons a day at 47 pico curies per liter and the illegal dumping issue needed a quick fix. This all scary stuff and LaDuke lays out the rationale for avoiding radioactive materials, especially since not all of it was making it to the landfills. Radioactive filter socks were thrown in ditches and kids found them to be interesting toys.

In that characteristic flash of wry humor, LaDuke quotes a female representative from the North Dakota Oil and Gas Industry. “Nuclear radiation isn’t so bad,” the rep said. “It’s not like Godzilla or anything. It’s more like Norm from Cheers, just sitting at the bar.”

“I want more of whatever psychedelic drug she’s taking,” LaDuke writes.

“In the Time of the Sacred Places” describes two paths to the future. One is scorched and one is green, and the Anishinaabeg would have to choose. (So do we all) Ancient teachings speak of a mandate to respect the sacred. In the millennia since the ancient prophecy, sacred Beings still emerge. LaDuke writes that they emerge in “lightning strikes at unexpected times, the seemingly endless fires of climate change, tornadoes that flatten” and floods.

As the Haudenosaunee teaching says, “...Our future is seven generations past and present.” We must assume responsibility. LaDuke’s fine book is our map.

REVIEW ABOVE Written by: Georgianne Nienaber, Writer and author

Indigenous Women Telling a New Story of Energy

The current story being told by our energy policies, practices and industry are devastating the land and changing climate. This program is an engaging and entertaining call to action for a new energy story that protects our land and its people.

If we need a new story for energy, we likely need new storytellers. Energy stories told by Indigenous women seek to carry forth the wisdom from their ancestors and combine it with the intelligence available to us today.

Indigenous Women Telling a New Story of Energy

Posted: May 4, 2016 at 8:30 am by KGNU, in A Public Affair, Featured

The current story being told by our energy policies, practices and industry are devastating the land and changing climate. This program is an engaging and entertaining call to action for a new energy story that protects our land and its people.

If we need a new story for energy, we likely need new storytellers. Energy stories told by Indigenous women seek to carry forth the wisdom from their ancestors and combine it with the intelligence available to us today.

Winona LaDuke

Winona LaDuke (White Earth Ojibwe) is an internationally renowned activist working onissues of sustainable development, renewable energy, and food systems. She lives and works on the White Earth reservation in northern Minnesota, and is a two-time vice presidential candidate with Ralph Nader for the Green Party. As Program Director of Honor the Earth, she works nationally and internationally on the issues of climate change, renewable energy, and environmental justice with Indigenous communities. And in her own community, she is the founder of the White Earth Land Recovery Project, one of the largest reservation based non-profit organizations in the country.

Beth Osnes. Writer, narrator and co-producer

Beth Osnes is a professor of theatre and environmental studies at the University of Colorado in Boulder where she is co-founder of Inside the Greenhouse, an initiative to inspire creative climate communication (www.insidethegreenhouse.net). With Adrian Manygoats, she helped found the Navajo Women’s Energy Project. For the last fifteen years she has worked in communities around the world using performance as a tool to help women empower their own voices for positive social change.

Adrian Manygoats – Co-producer

Adrian Manygoats (Navajo) was born and raised on the Navajo Nation, in Tuba City, Arizona. She is the Incubator Coordinator for the Native American Business Incubator Network (NABIN) at the Grand Canyon Trust. Prior to working with the Trust, Adrian co-founded the Navajo Women’s Energy Project and helped establish the non-profit organization Elephant Energy on the Navajo Nation. From 2013 to 2015, she operated with a team of organizers and community leaders in Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah to make affordable solar technology available to people without grid access.

Tom Wasinger – Editor, composer

Tom Wasinger is a self-educated multi-instrumentalist, vocalist, music producer, music arranger, composer, and educator based in the mountains outside of Boulder, Colorado. He has received three Grammy Awards for his work as a music producer/arranger/composer: The first in 2003 for Beneath the Raven Moon byMary Youngblood, the second in 2007 for Dance With the Windby Mary Youngblood, and the third in 2009 as producer/arranger for the compilation Come to Me Great Mystery by various Native American artists. He has also received four A.F.I.M. (American Federation of Independent Music) Indie Awards and six Nammy awards from the Native American Music Association as producer/arranger.

Guardians of the Planet: 10 Women Environmentalists You Should Know Guardians of the Planet: 10 Women Environmentalists You Should Know

Miigwech! How humbly honored I am to be listed with these amazing women: Kate Sessions, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Rachel Carson, Dian Fossey, Jane Goodall, Sylvia Earle, Wangari Maathai, Vandana Shiva and Isatou Ceesay.

Guardians of the Planet:

10 Women Environmentalists You Should Know

Posted on April 9, 2016 by Katherine

"During April's Earth Month, we're celebrating the incredible women who are working to protect the environment and all of the creatures which share our planet. From groundbreaking primatologists to deep-sea explorers to determined activists, each of them has changed the way that we see the world — and our role in protecting it. Equally importantly, these women have shown all of us that we have an effect on the health of our plant: from the smallest decisions of our day-to-day lives to international policy — each of us can make a difference.

Below we share the stories of ten women and explore their contributions to making a greener and healthier world. And, if you'd like to learn more about any of the featured women or introduce them to children and teens, after each profile we've shared several reading recommendations for different age groups, as well as other resources that celebrate these remarkable women.

To discover fictional stories that show young readers how everyone can make a difference in making the world a little greener, check out our blog post, Mighty Girls Go Green: 20 Girl-Empowering Books for Earth Month.

To learn about more trailblazing women, don't miss the first post in our Women You Should Know blog series: Those Who Dared To Discover: 15 Women Scientists You Should Know."

Winona LaDuke (b. 1959)

American activist Winona LaDuke learned early in her life about the challenges facing Native Americans: her father, an Objibwe man from Minnesota's White Earth Reservation, had a long history of activism relating to the loss of treaty lands. But within her tribe's traditional connection to the land, she also saw the potential for a new model of sustainable development and locally-based, environmentally conscious production of everything from food to energy. Her non-profit the White Earth Land Recovery Project has revived the cultivation of wild rice in Minnesota, and sells traditional foods under its label Native Harvest. She's also the cofounder of Honor the Earth, a Native-led organization that provides grants to Native-run environmental initiatives. "Power," she says, "is in the earth; it is in your relationship to the earth." By providing a model for that relationship, she hopes that other peoples, as well as Native American tribes, can see the value of sustainable, connected living.

Ralph Nader Radio Hour: Winona LaDuke, Kai Newkirk

Ralph Nader Radio Podcast: Winona LaDuke, Kai Newkirk Released Apr 23, 2016 "In two very high energy and passionate interviews, Ralph talks to Winona LaDuke, about her fight to stop a tar sands pipeline from running through tribal lands in Minnesota ..."

Winona LaDuke, Kai Newkirk

In two very high energy and passionate interviews, Ralph talks to former Green Party running mate, Winona LaDuke, about her fight to stop a tar sands pipeline from running through tribal lands in Minnesota and Kai Newkirk, one of the organizers of Democracy Spring, a protest to highlight the corruption of money in politics.

Video Winona LaDuke at Wis. Loca Food Summit Jan. 15, 2016

Video Winona LaDuke at Wis. Loca Food Summit Jan. 15, 2016

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask at Lensic Performing Arts Center

LaDuke talked about climate change and climate justice in the indigenous peoples’ communities, followed by a conversation with Mililani Trask. This event was part of the In Pursuit of Cultural Freedom lecture series.

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask at Lensic Performing Arts, Santa Fe, NM on February 24, 2016

Winona LaDuke is an Anishinaabekwe (Ojibwe) enrolled member of the Mississippi Band of Anishinaabeg. She is an… Read full bio.

Mililani Trask is a Native Hawaiian attorney and founding mother of the Indigenous Women’s Network. She is widely… Read full bio.

About this Event

Winona LaDuke is an Anishinaabekwe (Ojibwe) enrolled member of the Mississippi Band of Anishinaabeg. She is an indigenous rights activist, an environmentalist, an economist, and a writer, known for her work on tribal land claims and preservation and for sustainable development. LaDuke talked about climate change and climate justice in the indigenous peoples’ communities, followed by a conversation with Mililani Trask.

This event was part of the In Pursuit of Cultural Freedom lecture series.

Audio from this Event

Videos from this Event

Winona LaDuke elsewhere on Lannan.org

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask, 2016, (Events)

Winona LaDuke, (Bios)

Winona LaDuke Lannan Podcast Episodes

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask, 24 February 2016 – Audio

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask, Talk, 24 February 2016 – Video

Winona LaDuke with Mililani Trask, Conversation, 24 February 2016 – Video

VIDEO: Winona LaDuke (Honor the Earth) takes on Foreign Oil #Enbridge

FOOD + WATER | EARTH - The Battle to Protect our Lands, and Water from Extreme Extractions.

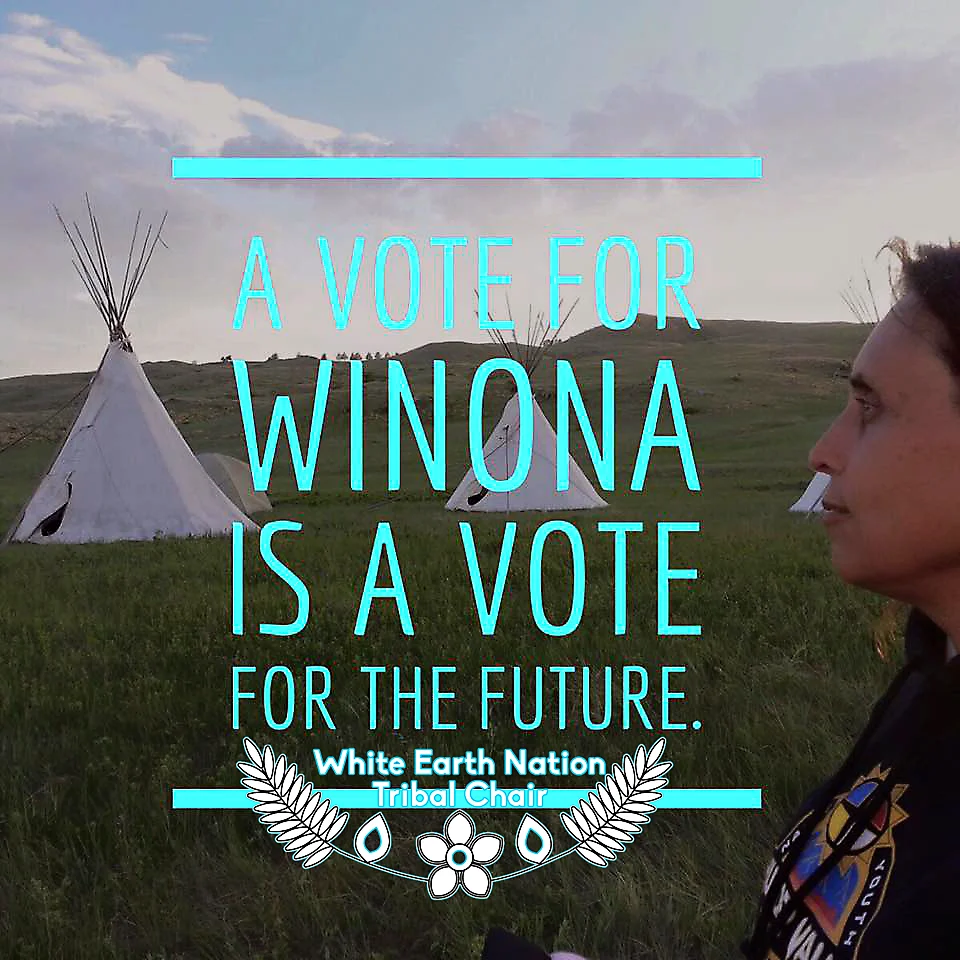

WHY a vote for Winona LaDuke for White Earth Tribal Chair is a Vote for our Future

FOOD + WATER | EARTH - The Battle to Protect our Lands, and Water from Extreme Extractions

WOMAN:: Anshinaabekwe teachings, of course we embody the Earth, but also we’re responsible for the water. The first water that baby is in a woman from the rain to the snow to the rivers (underground aquifers) to that water inside a woman. Those are all the different sacred waters.

WHY a vote for Winona LaDuke for White Earth Tribal Chair is a Vote for our Future:

It is important to come out and VOTE in the upcoming Primary April 5th, 2016. You can request an absentee ballot by writing a note to the:

**Election Board Box 10, Mahnomen Mn 56557

Our people are suffering. We are living in poor conditions because we continue to be robbed; our economy from the cradle to the grave is controlled by others. Today we face many challenges, and future generations will count on us to make a difference. This is our watch. We need to stop the poisons coming in to our community, stop the theft of our economy, land and lives, and protect future generations.

We need to work together.

All of us. There are a number of good people running for this office. The time is now to quit talking badly about each other. That’s how we stay oppressed. Let us put our minds together.

I have worked hard on the environment, on food, on energy and for our families.

- Anishinaabe Akiing fought the White Earth Land Settlement Act.

- The White Earth Land Recovery Project is what I led for 25 years and bought back 1400 acres held by a land trust on the reservation- lands open to tribal members. Native Harvest sells maple syrup, wild rice from the reservation.

- I worked with others to create Niijii Radio, the only independent tribal radio station in Minnesota

- I’ve worked with our tribal members and others to defend our land from genetically engineered wild rice and oil pipelines and to honor the 1855 treaty.

- I have testified at Congress and the Minnesota Legislature, and United Nations, and I can write laws and regulations. And I can work with people.

AGAIN:

A vote for Winona LaDuke for White Earth Tribal Chair is a Vote for our Future: It is important to come out and VOTE in the upcoming Primary April 5th, 2016. You can request an absentee ballot by writing a note to the:

**Election Board Box 10, Mahnomen Mn 56557

Spread the word, download, print and distribute

Article: Can't keep a good woman down: Winona LaDuke

“I became a casualty of the PTSD of the modern Indian Wars,” she writes in the introduction to her forthcoming book The Winona LaDuke Chronicles

"I was taught that cultural expression is the beauty of life and what distinguishes us as humans. … My family has always been interested in people who had courage, who persevered, who kept something valuable of their culture. That's where I come from. Those are the glasses I'm looking through." -- Winona LaDuke

Order at :: www.WinonaLaDuke.com

Q&A: Winona LaDuke - The Nation

Q&A: Winona LaDuke

A conversation with the two-time Green Party vice presidential candidate.

LF: So you decided to ride horseback along the route of the pipeline?

WL: On our reservation, the Enbridge Corporation is applying to nearly double the capacity of its Clipper line to 880,000 barrels per day—that is bigger than Keystone—and they want to build a third pipeline called Sandpiper next to our largest wild rice bed, to carry hydro-fracked oil from the Bakken oil field [in North Dakota] to Superior, Wisconsin. That amount of oil going across northern Minnesota—land of 10,000 lakes—would make this an oil superhighway. I had this dream that we should ride our horses against the current of the oil.

After that, we were invited to ride horse [into Washington]. It was an amazing spiritual experience. Nine teepees on the Mall, saying no to dirty oil and no to climate change, urging President Obama to do the right thing.

Read more: http://www.thenation.com/article/qa-winona-laduke/

How do we grieve the death of a river?

How do we grieve the death of a river? Written by Winona LaDuke

"Our people blocked the road. When the troops arrive, we will face them.”– Ailton Krenak, Krenaki People, Brazil

This eighteen months saw three of the largest mine tailings pond disasters in history. Although they have occurred far from northern Minnesota’s pristine waters, we may want to take heed as we look at a dozen or more mining projects, on top of what is already there, abandoned or otherwise. These stories, like many, do not make headlines. They are in remote communities, far from the media and the din of our cars, cans and lifestyle. Aside from public policy questions, mining safety and economic liability concerns, there is an underlying moral issue we face here:the death of a river. As I interviewed Ailton Krenak, this became apparent.

The people in southeastern Brazilian call the river Waatuh or Grandfather. “We sing to the river, we baptize the children in this river, we eat from this river, the river is our life,” That’s what Ailton Krenak, winner of the Onassis International Prize, and a leader of the Indigenous and forest movement in Brazil, told me as I sat with him and he told me of the mine waste disaster. I wanted to cry. How do you express condolences for a river, for a life, to a man to whom the river is the center of the life of his people? That is a question we must ask ourselves.

November 2015’s Brazilian collapse of two dams at a mine on the Rio Doco River sent a toxic sludge over villages, and changed the geography of a world. The dam collapse cut off drinking water for a quarter of a million people and saturated waterways downstream with dense orange sediment. As the LA Times would report, “Nine people were killed, 19 … listed as missing and 500 people were displaced from their homes when the dams burst.”

The sheer volume of water and mining sludge disgorged by the dams across nearly three hundred miles is staggering: the equivalent of 25,000 Olympic swimming pools or the volume carried by about 187 oil tankers. The Brazilians compare the damage to the BP oil disaster, and the water has moved into the ocean – right into the nesting area for endangered sea turtles, and a delicate ecosystem. The mine, owned by Australian based BHP Billiton, the largest mining company in the world, (and the one which just sold a 60-year-old coal strip mine to the Navajo Nation in 2013) is projecting some clean up.

Renowned Brazilian documentary photographer Sebastiao Salgado, whose foundation has been active in efforts to protect the Doce River, toured the area and submitted a $27 billion clean-up proposal to the government. “Everything died. Now the river is a sterile canal filled with mud,” Salgado told reporters. When the mining company wanted to come back, Ailton Krenak told me, “we blocked the road.”

They didn’t get the memo.

- Read more at: http://americanindiansandfriends.com/news/how-do-we-grieve-the-death-of-a-river-written-by-winona-laduke#sthash.oVTqm8uZ.dpuf

WOMAN ... WINONA LADUKE ABOUT: FOOD + WATER | EARTH

Winona LaDuke, WOMAN, In life, one may not always be sure of their path but for "the signs from above, Honor the Earth repeated, 'trust the process and you'll find what you're looking for.' - We can transition elegantly into a new era, living a good life with the Earth, and water. Let’s be someone that our future generations can depend on, and thank us for.

Photo credit: Keri Pickett | Twitter @KeriPickett

WOMAN

WOMAN is a collection of short films that profile extraordinary women as they push forward the front-lines, around the world. This collection is in development at the moment and will be available to the public in the coming future on a digital platform that allows women and men to explore the feminine experience on earth. We investigate the underlying issues confronting humanity to deepen our understanding of the challenges that bind us all. And through these stories, we aim to shift the prevailing gender paradigm and re-write the inaccurate notions of a woman’s role. This action is a vital avenue toward a more empowering and integrated future.

FOOD + WATER | EARTH

"How do you restore a wild bed?" "Can you tell me how you can do that?" Winona LaDuke during the Enbridge PUC Meeting in McGregor

WINONA LADUKE TAKES ON FOREIGN OIL

"Anshinaabekwe teachings, of course we embody the Earth, but also we’re responsible for the water. The first water that baby is in a woman from the rain to the snow to the rivers (underground aquifers) to that water inside a woman. Those are all the different sacred waters." Winona LaDuke

ENBRIDGE IS CATASTROPHIC:: We have a public policy crisis in the State of Minnesota. We are like the rest of you, we have lived our entire life in the petroleum era. We all use oil. We get that. But we are demanding and expecting a plan, a good plan, is a graceful and elegant transition out of it. Because the fact is what remains in the petroleum era is going to kill us.

Enbridge has not worked on a plan when there is oil leaks and when it would leak in a wild rice lake, even though scientific reports show they have a 57% chance at a catastrophic leak. So Enbridge messaging is that they, “strive for prevention ...,” interesting Enbridge fantasy because prior to a leak the fact is that even though these are areas are delicate aquatic eco system, Enbridge has no training or thought process in their planning to, “restore a wild rice bed,” in the watersheds. Our manoomin, the food that grows on the water, wild rice watershed, and beds are “not,” replaceable. Once they are destroyed, there is no going back to fix this destruction.

We profiled Winona LaDuke as part of our WOMAN collection. She's leading Honor The Earth and her wider community in a battle to stop Canadian oil corporation Enbridge Energy Partners and the Koch Brothers. Saying 'no' to business as usual isn't easy, but clean water and a safe environment are at stake.

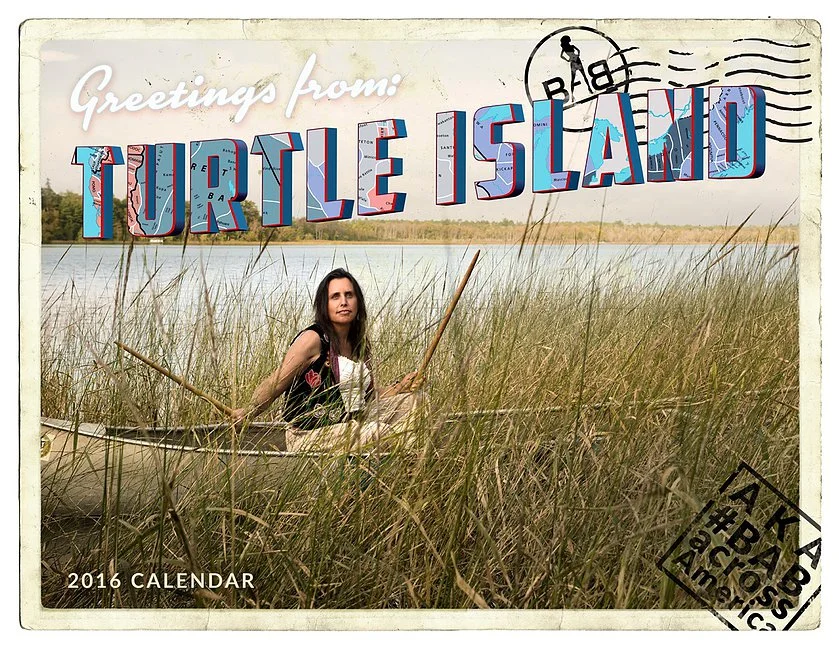

2016 Babes Against Biotech Calendars featuring Winona LaDuke

2016 Babes Against Biotech Calendars Pre-sale Now!

Support our stand for renewable, ecological agriculture, sustainable food systems, indigenous rights and social justice. Live your #BABlife every day in 2016!

We are very grateful to announce our 2016 Cover Role Model Winona LaDuke, internationally renowned activist, environmentalist, economist, and writer, known for her work with indigenous rights, land protection, and sustainable development. A former Green Party Vice President candidate, Winona is continuing to lead today by setting an example for all generations of devotion to the greatest good and human, indigenous and environmental justice for all.

Support our stand for renewable, ecological agriculture, sustainable food systems, indigenous rights and social justice. Live your #BABlife every day in 2016!

We are very grateful to announce our 2016 Cover Role Model Winona LaDuke, internationally renowned activist, environmentalist, economist, and writer, known for her work with indigenous rights, land protection, and sustainable development. A former Green Party Vice President candidate, Winona is continuing to lead today by setting an example for all generations of devotion to the greatest good and human, indigenous and environmental justice for all.

An Interview with Winona LaDuke by Yes! Magazine

An Interview with Winona LaDuke

On Wild Rice, Wind Power, Thunder Beings, Self-reliance, and our Covenant with the Creator

Sarah van Gelder posted Jun 17, 2008

Winona LaDuke and her son, Gwekaanimad, during a visit to the Suquamish Tribe’s Clearwater Resort in Washington state. Winona LaDuke is an Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) and the executive director of Honor the Earth, and founding director of White Earth Land Recovery Project. Photo by Harley Soltes for YES! Magazine

Sarah van Gelder: Could you tell me about your background?

Winona LaDuke: My father was Anishinaabe and my mother was a first-generation Russian/Polish Jew from New York. Both were involved with social movements—the Native American movement, farmworkers’ movement, poor people’s campaign, and the environmental movement.

I’m Bear Clan from the White Earth reservation, which is located between Bemidji and Fargo. My parents met because my dad was selling wild rice. I am part of a wild ricing culture. We are not rich in money, but we are wealthy in rice and other traditional foods. Sun Bear was my father’s name, and he used to have a saying: “I don’t want to hear your philosophy if it doesn’t grow corn.”

Sarah: You have focused much of your work on food and energy. What is your approach to these two basics?

Winona: Well first, we have to relocalize our economies. That doesn’t mean no imports and exports. But whether it’s food or energy, we’ve got to cut consumption; we’ve got to be responsible and efficient about what we use; and we’ve got to produce energy and food locally as much as you can.

There’s a phrase in Ojibwe, ji-misawaanvaming, which means something like positive window shopping for your future. We need to ask what our community is going to look like 50 or 100 years from now.

I’ve worked in my own community since 1981. We tried waiting for the federal and state government to take care of things, and if we had not taken action, we would still be waiting and I’d probably have a big ulcer from complaining, or kvetching as we say in Yiddish. We decided instead to put our hearts and minds together. We may not be the smartest, or the best looking, or the richest, but we are the people who live here. We decided we wanted to make decisions about the future of our community.

Sarah: What do your teachings tell you about creating that future?

Winona: We have a lot of teachings and language about how a people can live a thousand years in the same place and not destroy things. The phrase anishinaabe akiing, for example, means the land to which the people belong. It’s not the same thing as private property or even common property. It has to do with a relationship that a people has to a place—a relationship that reaffirms the sacredness of that place.

All our places are named. Near Thunder Bay, Ontario, is “The Place Where the Thunder Beings Rested on their Way from West to East.” We go there to do vision quests, to reaffirm our relationship with that power, and to offer our gifts to the thunder beings and the part they played in our creation. That place, and the places where our people stopped on their migration—all these places are named—and they have a resonance with us.

In all our teachings we understand that all the creatures are our relatives, whether they are muskrats or cranes—whether they have fins or wings or paws or feet. And in our covenant with the Creator, we understand that it is not about managing their behavior—it’s about managing ours, because we’re the ones who cause extinction of species. We’re the youngest species, and we don’t necessarily have the most smarts. We’ve bungled up along the way, and we acknowledge these mistakes in our stories and in our history as Indian people. The question is whether you have the humility and the commitment to get some learning out of these experiences.

Winona LaDuke. Photo by Harley Soltes for YES! Magazine

Sarah: What happens when this land ethic and this humility bump up against the dominant culture?

Winona: Ninety percent of the land on our reservation is held by non-Indian interests. We had the misfortune of having a neighbor who lived just to the south of us named Frederick Weyerhaeuser. We had fine white pine on our reservation, and he built his empire off of the land of the Ojibwe people in northern Minnesota.

And that is how some get rich and some get poor. It’s important to remember that most of these guys did not get rich by spinning flax into gold. They took someone else’s land, and they took someone else’s wealth.

That place known as The Place Where the Thunder Beings Rest isn’t called that now. It’s now called Mt. McKay. I don’t have a problem with Mr. McKay, but I do have a problem with this practice of naming large mountains after small men. How could we name something as immortal as a mountain after something as mortal as a human?

This could be fixed. Just look at Ayers Rock in Australia. It’s called Uluru now, because that’s its traditional name. Mt. McKinley in Alaska is now called Denali. The country of Rhodesia is now called Zimbabwe. It’s not disastrous to rename.

Sarah: Can you tell me about how wild rice is harvested?

Winona: We go up on the lake and we put our asemaa, our tobacco, on it. My son is my ricing partner, and we canoe through our rice beds. I used to push him, but he got too big, so now he pushes me out there, and I knock rice into the canoe with two sticks.

The rice grows on our lakes and rivers—some is fat and some skinny, some short, some tall. Some grows in muddy waters, some looks like a bottle brush, and some looks all punked out. That’s called biodiversity. It means not all the rice ripens at once. Some gets knocked off by wind. Some gets a blight, some doesn’t get a blight. The Irish potato famine should have taught us that agricultural monoculture is dangerous—but so is a social monoculture (or you could say, mall-culture).

The anthropologists used to come out and watch us manoominike—harvest the rice. After we rice in the morning, we bring our rice in and let it dry. We parch it over a fire, and we dance on it to get the hulls off, and then winnow it in a basket. We pretty much do the same thing today using wood fires as we’ve always done—we’re an intermediate technology people.

Ojibwe is a language of 8,000 verbs. The word for “work” is a strange construct for us. It doesn’t mean we aren’t a hard-working people, but in our language, the word is anokii, which means that whether you are fishing or weaving a basket, what you are doing is living—which is not the same thing as being paid a wage to do something.

After the harvest, we have a big feast, and we dance and tell stories. The anthropologists watched us, and they didn’t like that. They said we would never become civilized because we enjoyed our harvest too much. We did too much dancing, too much singing.

When you no longer enjoy your relationship to your food, to your plant relatives, to the harvest, to the dancing and singing—when you end up with a harvest that has no relationships or joy, I think that must be the mark of civilization and industrialized agriculture.

Sarah: What is the foundation for your economy? Do you sell your rice?

Winona: We sell our rice through Native Harvest. But for us, eating the rice is more valuable than selling it. Ensuring that our people have enough rice is what we’re after.

In our community, we don’t have a lot of wealthy people, but we have a lot of drums. We have a lot of songs. We have great maple syrup, harvested by hand and by horse, and boiled by wood. We are able to access the medicine chest of the Ojibwes. We have knowledge that is 10,000 years old. And we have the wealth of our relations to each other and to the natural world.

In our community, the stature of a human being is not associated with how stingy you are and how much you have in your bank account. It’s how much you give away, how generous you are.

It took the University of Minnesota about 40 years to figure out how to domesticate wild rice and cultivate it in rice paddies using chemicals and fertilizers, regulated so it could be harvested with a combine. They called it progress, declared it the state grain of Minnesota, and it took just a couple of years before Uncle Ben’s and the others took it over. Today, three quarters of all wild rice on the grocery shelf comes from giant rice paddies in California. No Ojibwe in sight.

Two Indians in a canoe can’t compete with a guy on a combine. One of my elders, Margaret Smith, and I went out to the lakeside because rice buyers were there trying to force the price they’d pay Indian people for rice down to 50 cents a pound. We said we’re going to pay a buck a pound. Margaret’s a good bluffer. They didn’t know how much money we had.

In 1986 we started fighting their right to call it “wild rice” because we think wild should mean something. In Minnesota you have to label rice as cultivated or wild, but in California or Oregon you can still sell cultivated rice as “wild” rice.

Our worst fears came true when the University of Minnesota cracked the DNA sequence of wild rice in the year 2000. They have not genetically engineered wild rice, but they want to reserve the right to do so. Our people do not believe that our sacred food should be genetically engineered, so we have been battling them for seven years.

Our foods are very much threatened, and this is an international issue for indigenous people.

After the harvest, we have a big feast, and we dance and tell stories. The anthropologists watched us, and they didn’t like that. They said we would never become civilized because we enjoyed our harvest too much.

Sarah: Besides protecting wild rice, what are you doing to bring back traditional foods?

Winona: We are growing more of our own food. About seven years ago, we got a handful of Bear Island flint corn from a seed bank and now we have about five acres of it. The corn is higher in amino acids, antioxidants, and fiber than anything we can buy in the store.

The traditional varieties of food that we grew as indigenous peoples—before they industrialized them and bred out much of the nutritional value—are the best answer to our diabetes. A third of our population is diabetic. We give elders and diabetic families traditional foods every month: buffalo meat, wild rice, hominy.

My 8-year-old, Gwekaanimad, and I started a pilot project with theschool lunch program after I saw that they were eating pre-packaged food from

Sodexho, Sysco, and Food Services of America. We try to give our school kids a buffalo a month and also some deer meat, some local pork, and local turkeys. We started growing and raising our own. It’s just a start. We had to de-colonize our kids, too, because they got used to thinking that their food was that other stuff.

We plowed 150 gardens last year on our reservation. I’m a big proponent of gardens, not lawns. It turns out in most reservation housing projects you can’t grow food. That spot in front of your house is where you park your car, or your dogs will trample it, or your cousin will drive over it. So we’re putting two-foot-tall grow boxes up there, and you can grow a lot of vegetables in them.

Our goal is to produce enough food for a thousand families in five years. And these foods we are growing in anishinaabe akiing are not addicted to petroleum, and they don’t require irrigation or all those inputs. These strong plant relatives just require songs and care for the soil. And in a time of climate destabilization, that is what you want to be growing. You don’t want to be guessing with some hybrid.

Sarah: What about relocalizing energy?

Winona: I’ve worked on energy issues pretty much my whole life. I’ve worked in Indian communities that are facing the biggest corporations in the world, and I’ve seen the effect of those corporations on land, people, and dignity.

Now, after 30 years fighting coal mines and uranium mines, to see the Bush Administration and Stewart Brand saying “nuclear power is the answer to climate change” I just feel that it’s time to move out of the box and into the next energy economy.

So now wind developers are coming into Indian country, which, it turns out, is rich with renewable potential.

Bob Gough from the Intertribal Council on Utility Policy says you’re either going to be “at the table” or you’re going to be “on the menu.” I want to see our Indian communities produce wind power on our own terms and own it. I want to see our young people benefit from it and train to be part of the next energy economy. We are a rural part of the Jobs not Jails movement that Van Jones and Majora Carter are leading in urban areas.

They say Native people in this country have the potential to produce one third of the present installed U.S. electrical capacity. When I first proposed a windmill on my reservation, members of the tribal council looked at me like I was nuts. But now one of my guys made me laugh, he said, “You know Winona, we used to think that you were crazy, but now we see that you were right. Someone had to stick their neck out!”

My tribe is putting up a 750 kilowatt wind turbine to power our tribal office building. Our organization put up a 250 kilowatt turbine. A tribe four lakes away has a lot of money, but not much wind; they asked us to site a two megawatt turbine for them on our reservation.

We are putting solar heating panels on the south side of our elders’ housing. It’s very simple technology; when the sun heats the panel up to about 90 degrees, the thermostat cranks on the blower fan, and blows hot air into your house. It works for us because even when it’s 20 below zero, the sun shines.

But we start with energy efficiency. I don’t support creating energy to feed an addict unless you deal with the addiction.

Sarah: What gives you hope to keep on with this work?

Winona: Life is good. We’ve been blessed with food that grows on water (wild rice) and sugar that comes from trees.

We’re technically one of the poorest counties in the state of Minnesota. My theory is, if we can do it, anybody can do it. It’s up to us—we’re making the future. If we’re waiting for somebody else to grow those gardens for us, well, we’re not high on their priority list. We have a shot at doing the right thing. So mino bimaadiziiwin (the good life), that’s the future we’re trying to create in our community.

Sarah van Gelder interviewed Winona LaDuke as part of A Just Foreign Policy, the Summer 2008 issue of YES! Magazine. Sarah is the Executive Editor of YES! Magazine.

Winona LaDuke on The Colbert Report

WINONA LADUKE

06/12/2008 VIEWS: 60,036